Saquib Salim

“The Indian Institute of Science owes its origin to the foresight and munificence of Mr. Jamsetjee Nusserwanjee Tata, who sometime in 1896 conceived the idea of vesting in Trustees certain houses and landed property in the city of Bombay representing a capital of thirty lakh of rupees, so that the net income, estimated at Rs. 1,25,000, might be applied towards the endowment of a Research Institute for India. The proposal was discussed in England and in India; a Provisional Committee presided over by the Vice-Chancellor of the Bombay University was nominated by Mr. Tata to promote it; and it was laid before Lord Curzon by a deputation, which waited upon him on 31st December 1898, the day after he had landed in Bombay.”

This is the opening of the Resolution of the Government of India, Home Department, dated Simla, the 27th May 1909, on the Establishment of the Indian Institute of Science.

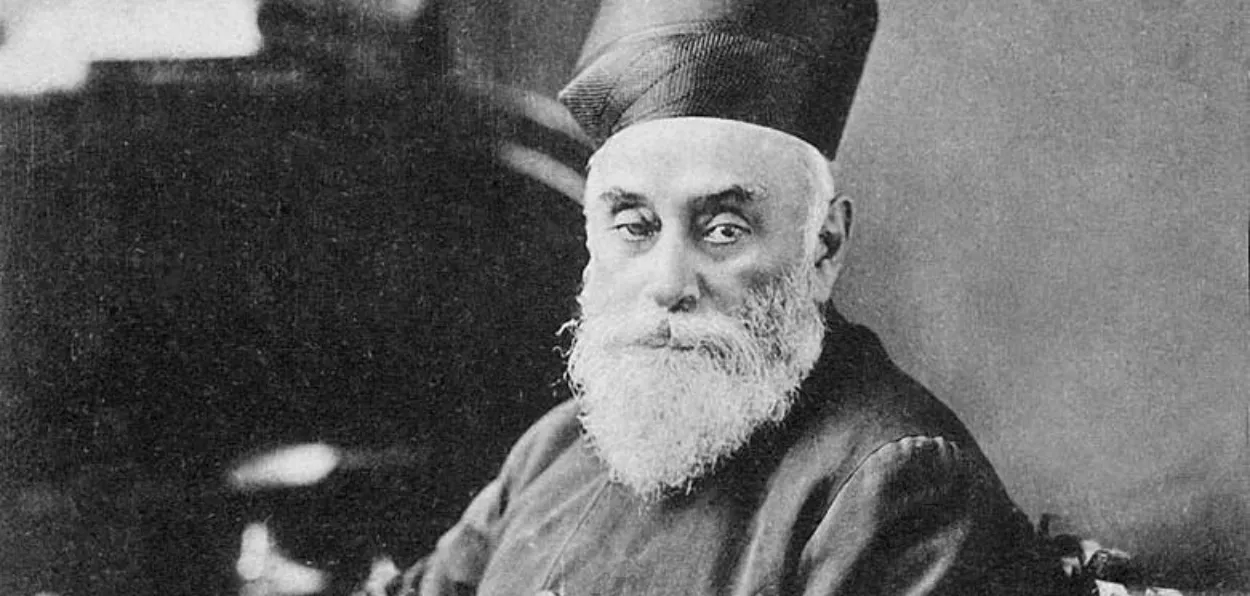

J. N. Tata, a successful businessman with a spirit to serve the nation, launched a movement to develop higher scientific research in India after listening to Lord Reay, the Governor of Bombay. The latter speaking as Chancellor of the Bombay University at its convocation in 1889 pointed out that the universities in India were no more than examination-conducting organisations as they did not contribute to knowledge production.

Tata was thoughtful; he started looking for a solution. He wanted India to develop as a center of science and learning. In 1892, he offered fellowships to meritorious but economically backward students to study in Europe.

F R Harris notes, “His primary object was to fit a larger number of Indians for the Higher Administrative and Technical Services, and to give them the opportunity of qualifying for the learned professions upon a scale hitherto unknown in India.”

It must be noted that almost 20% of the Indian ICS officers, doctors, and engineers started coming through this fellowship. The fellowship was like an easy loan where once students start earning they would pay back the money so that funds for future deserving students remain there. The intention was deeply patriotic.

Tata reportedly said in 1899, “Our young men have proved that they can not only hold their own against the best rivals in Europe on the latter’s ground but can beat them hollow….. Every Indian that gets into the Civil Service, I have calculated, effects a saving to this country of two lacs of rupees: that is what a civilian’s pay, allowance, and pension come to, most of which usually goes to Britain.”

.jpg) J N Tata's letter to swami Vivekananda

J N Tata's letter to swami Vivekananda

Tata was passionate about making India self-reliant in science and technology and was exploring all possibilities to achieve it. In 1893, Tata met Swami Vivekananda onboard a ship from Japan to Chicago when the latter was to make history through his speech. On 23 November 1898, Tata told Swami, “I trust you remember me as a fellow traveler on your voyage from Japan to Chicago. I very much recall at this moment your views on the growth of the ascetic spirit in India, and the duty, not of destroying, but of diverting it into useful channels. I recall these ideas in connection with my scheme of a Research Institute of Science for India, of which you have doubtless heard or read.”

Harris, in his biography of J. N. Tata, wrote, “Sir Dorabji Tata thinks that his father had at that time little hope of getting the Government of India interested in his scheme. In November 1898, Mr. Tata wrote a letter to Swami Vivekananda, adjuring him to rouse the country by a pamphlet relating to educational reform on ascetic lines, and offering to defray the expenses of publication.”

Tata’s hope was not misplaced. Swami did come to help and appealed to the nation to fund this proposed research institute. ThePrabuddha Bharata, a monthly journal started by Swami as the official organ of the Ramakrishna Mission, expressed its warm appreciation of the scheme in its editorial column of April 1899, during Swami Vivekananda’s lifetime.

The editorial by Swami Vivekananda said, “We are not aware if any project at once so opportune and so far-reaching in its beneficent effects was ever mooted in India, as that of the postgraduate research university of Mr Tata. The scheme grasps the vital point of weakness in our national well-being with a clearness of vision and tightness of grip, the masterliness of which is only equalled by the munificence of the gift with which it is ushered to the public….. If India is to live and prosper and if there is to be an Indian nation which will have its place in the ranks of the great nations of the world, the food question must be solved first of all. And in these days of keen competition, it can only be solved by letting the light of modern science penetrate every pore of the two giant feeders of mankind: agriculture and commerce...

"By some, the scheme is regarded as chimerical, because of the immense amount of money required for it, to wit about 74 lacs. The best reply to this fear is: If one man and he, not the richest in the land, could find 30 lacs, could not the whole country find the rest? It is ridiculous to think otherwise when the interest sought to be served is important.

Indian Institute of Sciences, Benaluru

Indian Institute of Sciences, Benaluru

“We repeat: No idea more potent for good to the whole nation has seen the light of day in modern India. Let the whole nation, therefore, forgetful of class or sect interests, join in making it a success.”

The appeal from Swami did not go in vain. Dewan of Mysore Sir Sheshadri Iyer, who had already told Tata that his state would help his venture, offered 371 acres of land in Bangalore, Rupees 5 lakhs, and an annual subsidy of Rupees 1 lakh for the institute. However, he later reduced it to Rs 30,000.

The government felt that the scheme was too ambitious and expensive. The official government report said, “In August 1899 Mr. Tata acquiesced in this decision and agreed to offer the University endowment “free from any stipulation as to personal or family advantage” The Government of India suggested to him that he should consult the Provisional Committee, and submit a definite scheme for carrying out the purposes of his endowment, revised in the light of opinions and criticisms which he had received.”

D. E. Wacha later commented, “He (J. N. Tata) was fully convinced that the future of the country lay in one direction in the successful pursuit of science which may in another direction be practically called to the aid of large industries which needed fostering and developing in India with her many rich but unexplored resources. The prosecution of science he believed would immensely benefit future generations of Indian humanity and conduce to their greater material prosperity. Science was the helpmate of industry. That was the root idea that had so long been revolving in his mind. That idea he resolutely resolved to put into practical execution. The more he revolved the idea in his head the greater became the desire to convert it into a reality.”

Here, it must be noted that the original Rupees 30 lakh sat aside for the institute and 1,25,000 annual income had almost doubled by 1909 when the institute was finally established. J. N. Tata died in 1904 but the Viceroy “received from Mr. R. J. Tata, the generous assurance that Mr. Tata’s sons were prepared to carry out the wishes of their father about the Research Institute.”

Sir Bhalchandra Krishna wasn’t very wrong when he said, paying tribute to J. N. Tata in 1905, “The magnum opus of his (J. N. Tata’s) life, which will always keep his memory green in India, is, undoubtedly, the Research Institute about the establishment of which the Government of India published a long resolution only a few days ago. In connection with this scheme, again, his thoroughness of action is well marked….

ALSO READ: Shami set the tone, Virat stood out and India stormed into CT final

"The scheme, as it was first conceived, was wider. But after a great deal of discussion and consultation with many eminent educationists and scientists amongst them the most prominent being Sir William Ramsey and Professor Mason, it was considerably narrowed to its present form…… This institute will always rewound to his credit as a cosmopolitan charity. It will promote education in its highest form and will direct the energy of our best intellects into new lines of research which are of the utmost importance to India.”