Saquib Salim

Alexander Fraser Tytler, Lord Woodhouselee in his 1791 authoritative text, the Essay on the Principles of Translation, described a ‘good translation’ as “That, in which the merit of the original work is so completely transfused into another language, as to be as distinctly apprehended, and as strongly felt, by a native of the country to which that language belongs, as it is by those who speak the language of the original work.”

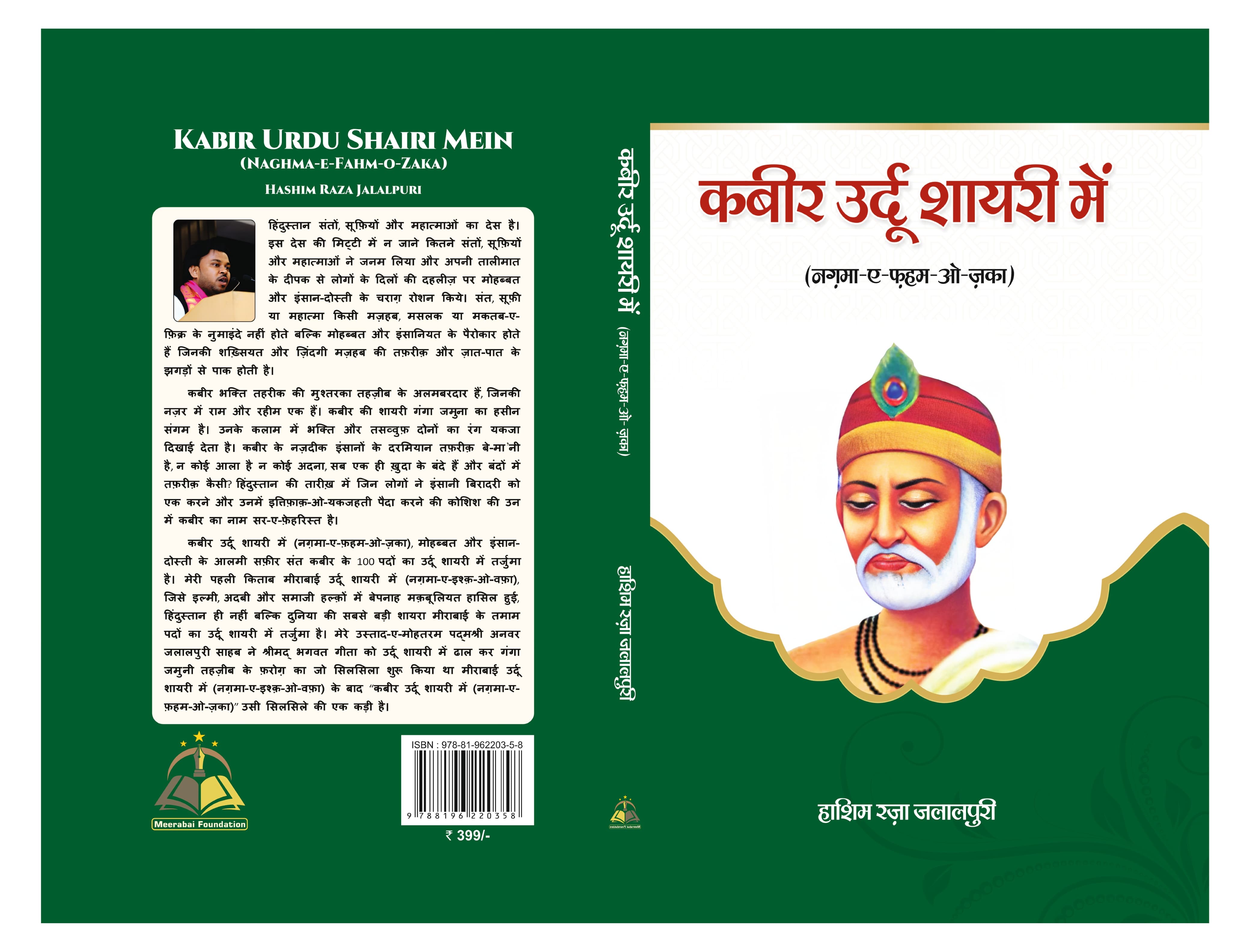

The recently published Urdu translation of the 15th century Indian mystic Kabir’s poetry by Hashim Raza Jalalpuri ticks all the requirements of a ‘good translation’. The book titled Kabir Urdu Shairi Mai: Naghma-e-Fehm-o-Zaka (Kabir in Urdu Poetry: Songs of Wisdom & Understanding) is a compilation of a hundred poems of Kabir in Urdu poetry.

This work comes as a sequel to his previous work, Mirabai Urdu Shairi Mai: Naghma-e-Ishq-o-Wafa, which was a translation of Mirabai’s poetry into Urdu poetry. Though there have been a few attempts at translating Mirabai and Kabir in Urdu before, Hashim’s translations are the first in poetic format. Thus, fulfilling one of the three laws of translation laid down by Tytler, which remained untouched in previous such works.

Cover of the book

Tytler stated, “The style and manner of writing should be of the same character as that of the original.” Hashim sticks to this law and adopts poetry as the style and manner of writing this translation. This sets him apart from Ali Sardar Jafri who attempted Kabir’s Urdu translation in a prose form.

Why is Kabir still relevant even after more than five centuries? Ali Sardar Jafri answers the question. Jafri writes that today we need the guidance of Kabir even more. Humans have reached the moon, built giant machines, and defeated diseases yet the world is divided into nations, religions, castes, and races that are always fighting with each other. Jafri believes therefore humans need a new belief in the creed of love through Kabir.

Why is there a need for an Urdu translation?

The language of Kabir was the 15th century dialect Sadhukkadi and today cannot be understood by most. As Kishwar Naheed, a prominent feminist Urdu poet, points out that younger generations should translate earlier works into more languages so that they can reach a larger public, Hashim has taken it upon himself to spread Kabir’s word to a larger readership.

Urdu poetry has a large audience in the Indian subcontinent. The book, apart from Urdu script, has been printed in Devnagri script as well. It is no secret that Urdu poetry is also listened to and shared by people who cannot read Urdu script. So, hopefully, this book can take Kabir’s wisdom to a much larger public.

Hashim translates, Kabir’s “na main deval na main masjid, na kaabe kailaas mai” into Urdu as:

Main na masjid, main na mandir, main na tanhaai mai huun

Main na kaaba, main na tiirath, main na unchaai mai huun

Any person who can understand Urdu/ Hindi will appreciate the ease and rhyme of the translation. Here Hashim keeps up to the third law of the translation proposed by Tytler, “The translation should have all the ease of original composition.”

Hashim translates Kabir’s, “Jaag pyaari ab kaa sove, Rain gai din kaahe ko khove” into Urdu as:

Ab to bedaar niind se ho jaa

Raat bhi dhal chuki hai din nikla

Hashim seems to stick to the first law of translation given by Tytler as well. Tytler writes, “The translation should give a complete transcript of the ideas of the original work.” Each translation of his gives a complete idea of the original, is easy to comprehend, and has a style equivalent to the original text.

There are several points in the book where the reader is forced to contemplate whether Hashim’s work should be called a translation as the Western world understands it or whether is it a ‘transcreation’, an Eastern tradition of retelling stories with new idioms. Judy Wakabayashi points out, “The Sanskrit anuvad — one of several equivalents for ‘translation’ in India—originally meant ‘repetition’ (a temporal concept), not interlinguistic transfer (a spatial concept)”.

Take a look at Kabir’s words, “Sarat suhagan hai paniharan, Bhare thaadh bin dor” and compare this with what Hashim has to say:

Usi ke des main ek husn o ishq ki devi

Wo bhar rahi hai waha dor ke bina paani

Hashim’s words completely explain Kabir here but in itself, this couplet is a work of poetry. It is not a translation in its literal sense but a transcreation as Mar Díaz-Millón and María Dolores Olvera-Lobo argue. They wrote, “Transcreation can be defined as a translation-related activity that combines processes of linguistic translation, cultural adaptation and (re)creation or creative re-interpretation of certain parts of a text.”

ALSO READ: EWS reservation was an old demand by secular leaders of India

The book on the one hand will introduce Kabir’s writings to a larger public on the other it also displays the art of poetry which Hashim has to display. The Urdu poetry of the book fulfills the most important requirement of Urdu poetry i.e., it has a rhyme that can be sung.