Awaz Team/Kolkata

Around 165 years ago, the last king of Awadh, Wajid Ali Shah’s kingdom was annexed by the British East India Company. Thereafter he made Kolkata his home. He reached Metiaburz, then a nondescript place on the southern fringes of the erstwhile capital of British India, was destined to shape up as ‘mini Lucknow’.

Over the generations people have drawn their understanding of the King from the Amjad Khan-starrer Shatranj Ke Khilari, a 1977 Satyajit Ray film, based on Munshi Premchand’s novel. Awadhi royals, however, brought subtle influences to the city of joy. The remnants are now part of Calcutta’s culture.

Khandan - I

Shahanshah Mirza is the great-great-grandson of the last Awadh King, one among the few descendants who didn’t leave the city that was the King’s home for all his remaining life. He is a well-known figure among Kolkata’s literati. He went to the city's best educational institutes and works as a senior officer in the central government. “We draw our ancestry from Prince Mirza Muhammad Babur who was one of the sons of Wajid Ali Shah. He was the only son who drew royal lineage from both parents,” Mirza tells this reporter.

Prince Babur was a trained physician who treated needy parents free of cost. He had four sons. His youngest son was Prince Ghazanfar Mirza who chose to live in Calcutta as he felt that Muslims have a better future in India than in Pakistan. “Prince Ghazanfar’s eldest son Sahebzada Wasif Mirza is my father. He is the patriarch of the family and president of the Awadh Royal Family Association. This was set up to look after the needs of the extended family,” Mirza adds.

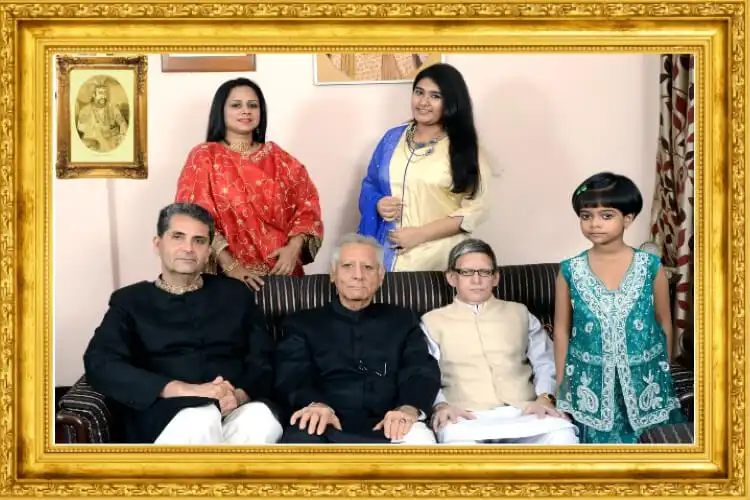

Dastarkhan has been replaced by dinning table: Shahanshah Mirza at dinner time with his family in Kolkata

Dastarkhan has been replaced by dinning table: Shahanshah Mirza at dinner time with his family in Kolkata

In Kolkata, there are over 20 members of the royal lineage which Mirza represents. Sahebzada Wasif Mirza, his father, is an octogenarian. He still receives a pension, now more a nominal gesture in terms of financial valuation. Over the years, even after Independence, once-influential Muslim families continued to migrate out of the region. This shoot of the king's descendants has stayed in.

Shahanshah Mirza has three siblings, including two sisters - both teachers. His wife runs a Montessori school. The elder daughter is working at a tea broking firm; the younger one is studying and aspiring to take up tennis as a career. “Our father got us educated to the best of his abilities as we realised that education is the only medium that can help us move up in life. Initially, I was to become a doctor,” says Mirza.

Mirza smiles when asked if the tradition of pehle aap, requesting an accompanying guest or friend to make the first move when something is offered, is still prevalent. “A lot of people make fun of the gesture. We, however, still hold traditional values with pride. Asking someone, aap kal aaoge is not the same as asking, aap kal aaiyegaa,” Mirza says.

In the family, Urdu words like, hammam and tashtari, are still preferred over their English synonyms of, bathroom and saucer. The daughters are also addressed aap. There’s an emphasis on having at least foundational knowledge of the Persian language.

There’s still a strong urge to follow traditional etiquette. “When we invite a guest, in a subtle way, we try to understand their food preference and get the cooking done accordingly. The guest is offered a place at the head of the table,” says Mirza. While the dastarkhwan (dining spread laid on the floor) has a table as a substitute these days, yet on special occasions meals are organised with sitting arrangements made on the floor. The rectangular cloth spread has couplets printed in honour of the guest, a gesture of hospitality.

Shahanshah Mirza

Shahanshah Mirza

“A lot of people associate Wajid Ali Shah only with Calcutta biryani (that has potato as an important ingredient). I feel sad and at times angry when I hear such comments. The King and the family’s contribution is tremendous. In many fields, you can see the impact,” says Mirza.

Wajid Ali Shah came to Calcutta in 1856 after being dethroned. He was imprisoned at Fort William before he settled in the city. His entourage, it's said, had around 500 people. Royal physicians, khansamas (butlers and servants), poets, maulvis (clerics), and others, needed in daily life, were part of this group.

The King’s stay encouraged Awadhi customs and traditions in the multicultural city, besides the introduction of a refined Urdu dialect. More people followed the king, once he settled in the region. Mushaira, ghazal, and other literary forms discovered new patronage. Awadhi dressing - sherwani, achkan, churidar, kurta-pyjama, sharara, gharara, became a part of the city's fashion. Metiaburz is now among Asia’s largest centres known for producing unbranded garments. The kite-flying got accepted as a leisure activity by the city's bhadralok (cultured) and zamindars. Besides Calcutta biryani, paratha, sheemal, roghni roti, shahitukra, shaami kebab, qorma - the Awadhi cuisine got absorbed in citizens’ diets for all times to come.

Kolkata is evolving, like many other cities. The story of the last king of Awadh is as pleasant as a fairytale to most people. Peaceful coexistence, observing Moharram, showing generosity in accordance with financial abilities, are some of the qualities that have remained. The family tree is intact. Members, now a diaspora, meet occasionally.

For the royal family, it’s about retaining a legacy, an identity. Mirza is often invited to represent Awadh royals. Durga Puja is the biggest festival in the city, and Mirzas, as part of the city’s gentry, are happy to visit friends on this occasion, as much as they are on Eid, Diwali, and Christmas.