Saquib Salim

Jaipur city’s M.I Road that connects important government offices is named after Mirza Ismail, a fact that is lost to many in the rat-race-driven generation. I visited the city in late 2019s and it is then that I decided to know more about this man. I was somewhat embarrassed to realize that despite having done my Master’s degree in modern Indian history, I didn’t know about this important Indian leader.

Mirza Ismail was one of the important voices among the Indian Muslims who had opposed the demand for Pakistan in the 1940s. For 15 years, he had served as the Prime Minister of Mysore, a state ruled by a Hindu and known for the patronage of the Hindu religion. He then moved to Jaipur, yet another state ruled by a Hindu ruler, as Prime Minister. Ismail was the Prime Minister of Hyderabad just before the independence, took on the communal forces unleashed by Razakars.

Ismail wrote, “I believe that there is ample room in this spacious land of ours for all our languages, creeds, and cultures to flourish in amity. India would not be half as interesting without such variety.” While he had been hailed by people, like M. Visvesavaray and C. V Raman, as one of the main architects in planning modern Bangalore, its urbanization and industrialization, Ismail took a special interest in preserving Hindu religion through promoting Sanskrit and ancient scriptures. His role in promoting and preserving the Sanskrit College of Mysore amidst the onslaught of ‘western modernists’ was universally praised by Hindu scholars like Jagadguru of Sringeri, the Parakala Swami of Mysore, and the Lingayet Jagadguru of the Murugi Mutt.

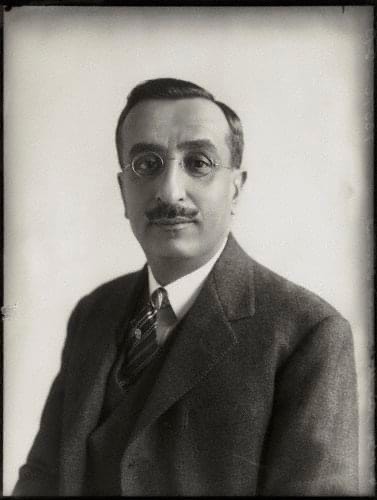

Mirza ismail

Ismail said, “Sanskrit is called a “dead” language, but in another and more real sense it is very much alive. It continues to sustain and enrich many living Indian languages from its vast storehouse of literature...... One cannot contemplate with equanimity, though happily, such an eventuality is improbable, the divorce of Sanskrit from the everyday life of the masses as with Latin and Greek in Europe. Light would have gone from the life of the people, and the distinctive features of Hindu civilization and culture which have won for it an honoured place in the world thought would soon be effaced from the life of the community to the great disadvantage of India and the world.”

Ismail resigned from the Premiership of Mysore after the death of Krishnaraja Wodeyar IV and was offered the post of PM at Jaipur state by Maharaja Man Singh II. At the time of his appointment, Jaipur was facing social, political, and economic problems. Ismail laid special stress on urbanization, education, and industrialization. His policies were so effective that his initial tenure of one year was extended to four. When Ismail agreed to serve the state for more than a year, Maharaja wrote to him, “I can’t tell you how happy I am that you have accepted my invitation to stay on as my Prime Minister for another two years. You have earned my implicit confidence and you may rest assured that you will always have my fullest support. No other Prime Minister in Jaipur has done so much to improve the tone of the administration and to inspire so much confidence in the hearts of the public.”

Ismail made it a point to invest in the development of Jaipur when, during the World War, the British wanted money in their coffers. He was a patriot who knew how to argue in support of Indians. His handling of the protests during the Quit India Movement ensured that the Indian nationalists were not penalized or targeted.

The New York Times reported: Jaipur thanks its Premier (Ismail) for its calm and wonders why the authorities elsewhere do not act as he does……. There has been no rioting or sabotage here. The police and troops have made no lathi charges, nor have they fired into crowds.”

Mirza Ismail with the Maharaja of Mysore

Ismail joined Nizam of Hyderabad as its premiere in August 1946. Those were the turbulent times as India was on the verge of attaining freedom and Jinnah was trying hard to persuade Nizam into joining his camp. The appointment of Ismail, a proven secular Indian nationalist, was a shocker for Jinnah. How could Jinnah tolerate the appointment of a man, who, in 1941, had written to him, “You invite me to join the Muslim League? I wish I was in a position to do so, but, you will no doubt realize, my lifelong association with a Hindu Maharaja and my long service in a Hindu State where I have received the most loyal cooperation from my Hindu fellow citizens throughout my official career, prevent me from identifying myself with a political organization which is avowedly anti-Hindu in its aims and objects. My endeavour will be to work-in so far as it lies in my power—for communal concord while safeguarding the legitimate interests of my own community to the fullest extent.”

Jinnah wrote to Nizam asking not to appoint Ismail as his Prime Minister and later visited him to press his demand. When Nizam ignored his suggestion, Jinnah warned him that Muslim League would not help Hyderabad in the future. Jinnah took Ismail’s appointment as a personal defeat. Nawab Hosh Yar Jung wrote about the meeting, “the Quaid-i-Azam has had the lesson of his life. But we know that this does not end here. He is a very vindictive man, and immediately after the interview, he started long conferences with local leaders.” Jung was not wrong.

Ismail later wrote that it was difficult working with the Nizam, “who was bent upon independence. Even more so were that wretched band of foolish Muslims called the Ittihad-ul-Muslimeen.” The communalists Ittehad-ul-Muslimeen accused in their paper, “Sir Mirza is seen in corridors flirting with Congress members and greeting them with folded hands like Hindus. Sometimes he was heard saying “namaste” or “namaskaram.” He is also believed to have said that the Hindus, being in a great majority, would rule in the long run despite all difficulties.” Ismail was an object of hate for the pro-Pakistan element.

In his resignation letter to the Nizam, Ismail wrote: “I (Ismail) have had the misfortune to find myself opposed at every turn by a certain section of the local Mussalmans, who, in my opinion, are set on a course that is suicidal to the State……… while a word from you would have stopped the campaign at once, you have maintained silence, and the agitators have given the impression that they enjoy Your Exalted Highness’s goodwill and patronage.”

Ismail could not prevent the partition and bloodshed it accompanied. In 1954, he reflected upon the tragedy and wrote: “I was strongly opposed to the division of India. It cannot be denied at the partition of the country has resulted in the weakening of both the parts, India less, perhaps, than Pakistan……….. It has made the position of the Muslim community within the Republic of India, numbering some 40 million, extremely difficult and embarrassing.” Regarding Pakistan Ismail wrote, “the cry of an unthinking section, and the recommendation of an advisory committee, for a constitution based on the Shariat (Muslim law) or Islamic principles is not a healthy sign. As a Muslim, I respect these principles, but one has to consider how far they apply in detail to modern conditions. The increasing influence of the fanatical element on the masses augurs ill for Pakistan. It is never safe or wise to project religion into politics and allow politics to masquerade in the guise of religion.”

Also Read: How a Hindu-Muslim dialogue averted a riot in Mumbai?

Today, this man who stood for everything Indian is known for, is nearly forgotten.

(Saquib Salim is a historian and a writer)