Sreelatha Menon/Thrissur

Long before Ratan Tata’s young protégé Shantanu Naidu turned his heartache for the lonely aged people into a start-up called Good Fellows under the Tata Trust, a community-led model of Good Fellows has been in force in Kerala. It’s meant for people who are terminally ill, bedridden, or suffering from illness beyond medicines and doctors.

The programme is backed by the Government and local self-governing bodies.

While Tata Good Fellows involves volunteers who visit aged people and spend time with them, the Kerala programme provides care specifically palliative care at the doorstep.

It involves regular home visits by dedicated nurses, doctors, and therapists besides young students and other volunteers to provide palliative care for those who are bedridden, in pain, beyond treatment, and left to die alone. It also involves training caregivers to manage illness and age-related conditions.

A Palliative nurse with a patient somewhere in Kerala

A Palliative nurse with a patient somewhere in Kerala

Primary Health Centers in all districts of Kerala have a palliative care unit comprising a doctor and a palliative nurse. They go on house visits and attend to terminally ill patients thrice a week. Needy people are identified and registered in each locality (wards).

Each health center in Kerala has an ANM (auxiliary Nursing midwife) trained in palliative care. The statewide project is led by allopathic, ayurveda, and homeopath doctors.

This is a unique system in the world, says Dr Divakaran one of the pioneers of the palliative care movement.

Whay is today known as the Calicut Model of Palliative Care started in 1993 when an anaesthesiologist Dr MR Rajagopal in the Calicut Medical College Hospital along with Professor Suresh Kumar and an activist Ashokan decided to help people in need of palliative care. They started from a small space adjacent to the operation theatre where patients identified by doctors as suffering from incurable diseases were brought to consultation.

Doctors felt they could not do anything on their own. So friends, their wives, volunteer nurses, and relatives of the patients also pitched in.

They soon realized that relatives of terminally ill patients could become partners in care if they are empowered, says Dr. Dvwakaran.

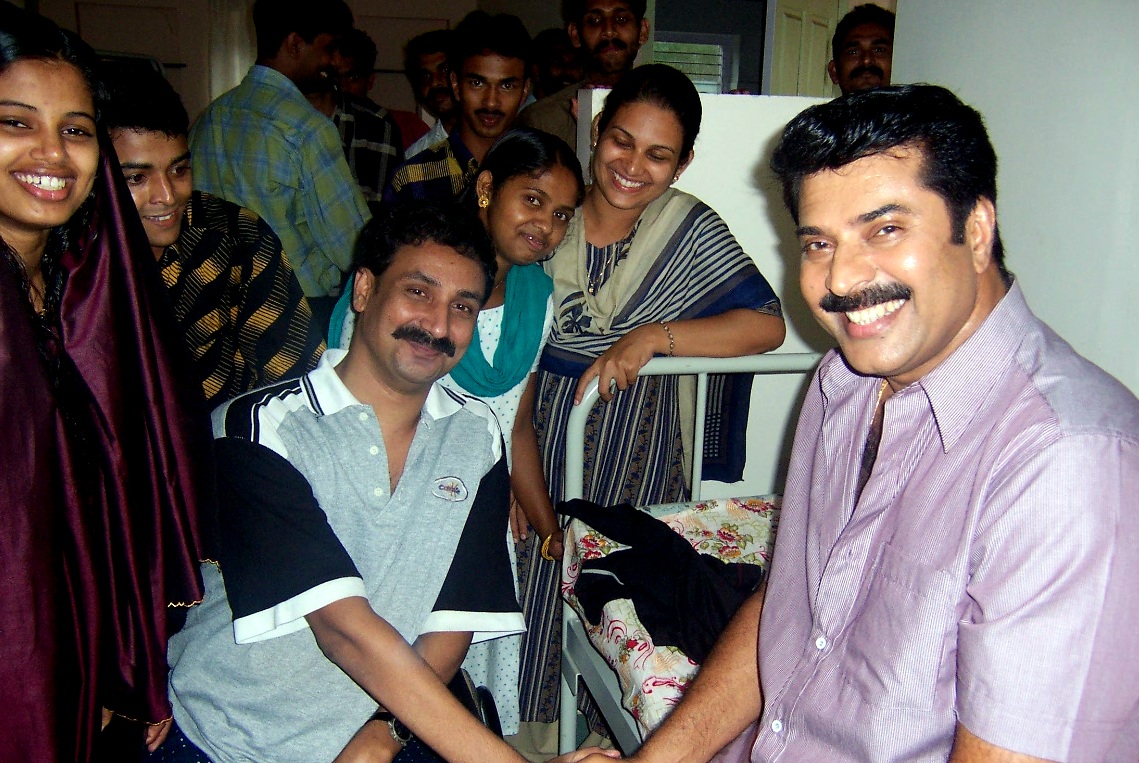

Volunteers with actor Mamooty

Volunteers with actor Mamooty

Thus, in a resource-poor country, a palliative care unit started functioning using the existing infrastructure facility in a government setup and filling the gaps with volunteers and partnerships with families of patients. This model was discussed in international forums and accepted as a unique model worldwide, says Divakaran who was then doing his masters at the Calicut Medical College.

The Bruce Davis Charitable Trust in the US sent a crore rupee to the society and soon a whole building in the medical college campus was given to the palliative unit.

The volunteers and nurses under the society would do house visits in the community, identify needy patients, and provide necessary care. Then the society started satellite centers in neighbouring Malappuram district, Manjeri, Wayanad, and Nilambur.

A People-Led Movement

At the Malappuram center, the palliative care model got a makeover as the Calicut model was turned upside down. Here people started taking a lead role in identifying patients and doctors took the back seat.

The doctor-led programme of Calicut suffered from the biases of doctors who restricted beneficiaries to only some diseases. In Malappuram the common man identified who was needy based on their suffering and not the name of their disease or condition, says Divakaran.

Pain and Palliative Care Society office

Pain and Palliative Care Society office

It became a popular movement funded and run by the community. Soon the district panchayat started setting aside money for the palliative care unit. This was the beginning of NNPC or the Neighbourhood Network in Palliative Care which later took shape across the state.

Today 230 NNPCs have come up across the state, says Dr Divakaran.

As per the Kerala Palliative care policy laid down In 2008, every PHC must have a palliative care unit and a trained ANM. About 2,000 nurses were recruited for this. Even now the palliative care programme is run not by Government funds but by local self-governing bodies and NGOs, says Dr Divakaran.

The Pain and Palliative Care Society in Thrissur for instance has a monthly expenditure of Rs 13 lakh and it raises it through donations. The PPCS takes care of 20,000 patients every month, says Dr Divakaran.

Palliative care involves consolation and comfort more than medicines. In Malayalam it is called santvana chikitsa … which is care , solace, and cheering up rather than medical treatment. And who can best cheer up those who have no hope, but children?

So youth is very much part of the palliative care movement in Kerala. Youth are being included through a Student Initiative in Palliative Care or SIP also through the National Service Scheme, says Dr Diwakar.

“Last year we visited 30 families as part of palliative care and met them again during Christmas and Onam and gave them gifts and chatted with them,” said Gopika an undergraduate student at St Aloysius College in Thrissur. It is a continuous intervention through NSS, she said.

Student volunteers as caregivers with medical staff

Akhil who got involved in palliative care as a student volunteer about 7 years ago, today heads the student initiative or SIP and runs orientation camps for student volunteers in different colleges in Thrissur. Our vision is to have a palliative care club in every college and connect it to various health centers and their care units, says Akhil. He says this model is to be replicated in the rest of the state.

Many students are interested and approach us either directly or through NSS. It is not for any professional gain but for purely personal achievement, he says.

ALSO READ: Kerala Palliative nurse Selvy recounts experiences of tending to people in pain

At present palliative care is being provided in various cancer hospitals like Tata Memorial Hospital and AIIMS in the country and a few states have even drafted a policy recently. Says Akhil who works for a health agency in Bangalore while running SIP in Kerala: “At least 95 percent of people in Kerala know that a palliative care programme exists. But if you ask anyone in Karnataka or Tamil Nadu, people are yet to know about it. It is not structured as it is in Kerala.”