Sabir Hussain/New Delhi

Most Indians know of Turtuk as a place that India had wrested from Pakistan during a battle along the Line of Control (LoC) in 1971.

Turtuk in India’s extreme north along the twisting Shyok river that cuts through the Nubra Valley among the towering Karakoram mountains is so nondescript that a tourist would simply pass by before the journey ends at the LoC about 15 km away.

Few know that Turtuk was also part of the ancient Silk Route and that its Muslim inhabitants are the Balti people who are now spread on either side of the LoC in the Baltistan region. Fewer still know about the composite culture and lives of the Balti people that have been shaped by the confluence of different cultures along the Silk Route.

Given its strategic location, Turtuk was out of bounds for most Indians and it was only in 2010 that it was opened for tourism but is still a relatively less explored area in Ladakh.

Things are changing, though. A family in Farol village of Turtuk is doing its bit to spread knowledge about Balti culture by converting a part of their house into a museum.

An old samovar at the museum.

An old samovar at the museum.

Mohammad Ali, a landlord, and his wife Rahim Bi’s seven children - four sons and three daughters – who have studied in different places in the country take turns to show visitors around the museum, depending on who is present at Farol.

In the summer of 2018, Mohammad Ali’s youngest son Wasim Yahya, then barely out of his teens was feeling restless because he “wanted to do something useful” but had no idea it would be.

“I had no idea what to do. Then I thought we could leverage our house which is almost 150 years old and has lots of antique items, some more than 200 years old, and turn it into a museum. I did not have a grand vision but our efforts have come out well,” 22-year-old Wasim, now pursuing a Masters's degree in Indian Institutes of Science Education and Research (IISER) at Pune told Awaz the Voice.

And so the Balti Heritage House and Museum was born.

But how did the word spread about a museum in a little corner of Baltistan in one of India’s most remote areas?

“There are a few guesthouses, homestays, and cafes on the road leading to our house. We requested their owners to recommend to their customers to check out our house. Slowly, tourists started coming and after a week their volume increased. The response was quite encouraging,” says Wasim.

People have to walk through cobbled alleys flanked by narrow irrigation channels amid expansive barley fields set against the backdrop of the mountains to reach the white and grey Balti Heritage House and Museum surrounded by apricot and apple trees. A courtyard leads to the house where a portion of it has been converted into the museum. A ticket for the museum costs Rs 50.

Also Read:Dr Noori Parveen, a boon for the poor in Andhra’s Kadapa

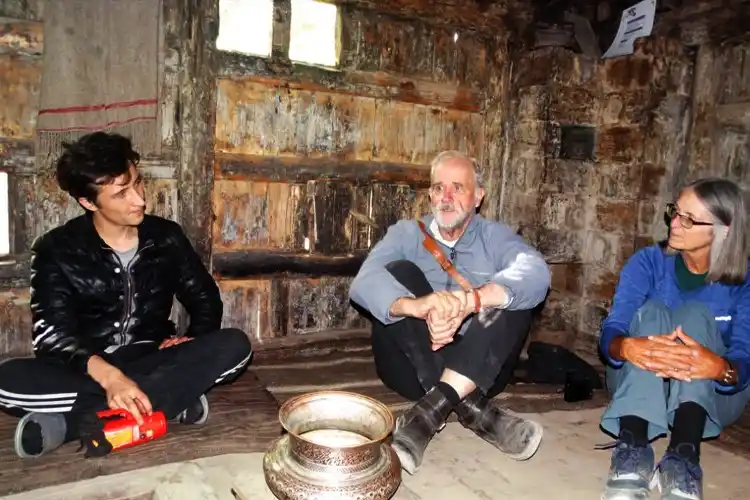

Foreign tourists at the Balti Heritage House and Museum.

Foreign tourists at the Balti Heritage House and Museum.

Several generations have lived for the better part of two centuries in the sprawling stone and wood house with low ceilings and very small windows to avoid cold air blowing in during winters. The gaps between the logs used to build the house have been sealed with apricot jelly that acts as putty. Apricot grows abundantly in Turtuk and almost every family owns at least a few trees.

Although Wasim was instrumental in setting up the museum, the rest of the family, including his brother Ghulam Hussain is now more involved in the project.

The only improvisation that the family has done is to install lights in the museum.

A wooden pillar in the museum which supports the ceiling has a knot of never-ending loops carved on it at the top. It is said to be a Buddhist (and surprisingly Celtic as well) endless love knot. It consists of two hearts interlaced which can be construed to represent unity and brotherhood.

In Balti culture, a never-ending loop is also a sign of prosperity and so is a strong pillar.

A pillar in the museum with never ending loops.

Inside, there are quite a few antique items like bows and arrows made of horns of ibex (mountain goat) and yak hair.

There are combs made of ibex horns and brooms made of yak hair. Yarns of sheep, yak, and pashmina goat are also on display. Balti people once used yak hair to make carpets.

On wooden racks inside the kitchen are vintage utensils such as large stone cooking pots, copper urns, and samovar (kettle) to make tea. There is also copper cutlery that has long gone out of fashion.

Stone pots that were once used for cooking.

“Locals no longer use copper cutlery because they are expensive. Coppersmiths in Turtuk still make such cutlery but it is mostly tourists who buy them for their novelty,” says Ghulam.

A trapdoor on the kitchen floor leads to a granary that was used to store grains.

A glimpse of Balti kitchen in the museum.

There is also a stone bunker that serves as natural cold storage in the Balti Heritage House and Museum. While many may be surprised about the need for cold storage in Turtuk, Ghulam explains why it was necessary.

“Summer temperatures can rise to uncomfortable levels in Turtuk. So cold storage was used to keep perishable food items in earlier times. It is only recently that refrigerators have come into use in Turtuk,” he says.

At just about 10,000 ft, Turtuk is lower than most other places in Ladakh which make the summer more intense. For generations now, the villagers have leveraged their rocky surroundings to build natural stone-cooling storage systems to preserve meat, butter, and other perishables during the summer. In the Balti language, the structure is called 'nangchung' which means 'cold house'. These stone bunkers are designed with gaps that allow cold air to pass through, keeping the goods cooler than the outside air temperature. Vegetation, which is denser in Tutruk than in other places in Ladakh, also helps in making the cold storage effective.

Also Read: AnsarAhamed, engineer who built a Rs 10-cr riding gear brand

On display in one of the rooms in the museum are traditional clothes, including winter clothing made mostly of wool and some made of sheepskin and fur. Like other items in the museum, these clothes are also very old, some dating back to almost 400 years, and have been handed down generations in the family.

“The winter clothing was also stored in the cold storage earlier because if those are kept outside for long they tend to wear away soon,” Ghulam explains.

Traditional Balti clothing.

Traditional Balti clothing.

Among other items are wooden jugs that were used to measure grains, a pair of scissors called chan-ma that was used to shear a mountain goat or a yak, a wooden weighing scale, and rope balls made of the hair of sheep, goats, and yaks.

The Balti Heritage House and Museum had just started gaining traction when the COVID-19 pandemic threw a spanner in the works as it throttled tourism for two successive years. A lockdown meant there was no movement of tourists. But with the pandemic on the wane, the family is now looking forward to the summer of 2022.

“We haven’t expanded the museum but this year an expansion is on the cards. There are plans to integrate the rest of the house into the museum. We will add more items to the collection. We will try to diversify the inventories and add a couple of sections for different kinds of items. We may even have a photo gallery,” says Ghulam.

An engraved urn in the museum.

An engraved urn in the museum.

There are only a few thousand families in and around Turtuk that makes the community a microscopic one in India.

The Balti Heritage House and Museum, the only one of its kind in India, is doing its bit to spread awareness about the community among other Indians.

For anyone who takes the trouble of visiting Turtuk, he or she will undoubtedly return with the scent of Balti culture.