Ajit Rai

The Ariana Cinema Square in Kabul downtown was a busy traffic junction of the city till recently. For decades this historical cinema, constructed in 1960 entertained the Afghans and stood a mute witness to the country's wars, people’s hopes dwindling between extremes and cultural changes. Today the posters of Bollywood films and American action films that once adorned this theater have been removed after it came under the Taliban rule. The doors of the theatre, at least for now, seem to have been closed, forever.

It pains to see that when the world is worried about Afghanistan after the Taliban captured the country no one seems bothered about the death of the Afghan cinema.

The return of the Taliban inevitably signals the threat of the destruction of Afghanistan’s art, literature, cinema, and secular culture. As the Taliban have expectedly banned cinema again, I am missing Iranian filmmaker Wahid Moussen's Gol Chehre (2011).

Women in Afghan Cinema

While there is no discussion on Afghanistan’s cinema in the world, surprisingly, no specific conversation has ever been heard in India about this, while India's historical and mythological ties with Afghanistan have been very deep. Many Indian directors have made successful films on Rabindranath Tagore's story Kabuliwala, first in Bangla (1957) by Tapan Sinha and later in Hindi (1961), including Hemen Gupta.

From Hollywood's The Kite Runner (2007) to Bollywood's Dharmatma (Feroz Khan, 1975), Khuda Gawah (Mukul Anand, 1992), Kabul Express (Kabir Khan, 2006), and many more films were made in Afghanistan. Indian films made in Afghanistan have never been good enough to be discussed.

The credit for bringing cinema to Afghanistan goes to King (Amir) Habibullah Khan (1901–1919), who first showed some films in the royal court with projectors. The projector was then called the ‘Magical Lantern’. There is also mention of the screening of a silent film for the general public in 1923 in the city of Paghman near Kabul.

The first Afghan film is considered to be Love and Friendship (1946). After that, many documentaries were made on Afghanistan and these would be shown before the feature films from India. After the civil war in 1990 and the Taliban assuming power six years later, the making and watching of cinema were banned.

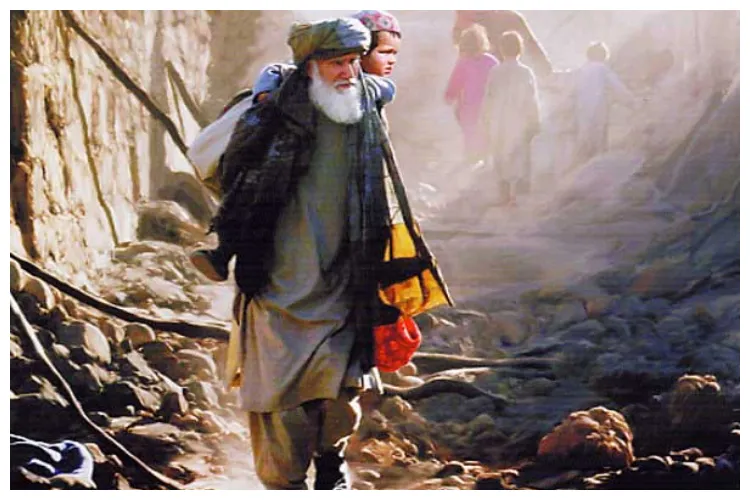

A scene from a film based on Afghanistan

Afghanistan's cinema came up for discussion when famous filmmaker Mohsin Makhmalbaf's film Kandahar (2001) was shown in more than 20 film festivals around the world. The film drew worldwide attention to a nearly forgotten country, Afghanistan. Later, his daughter's film At Five in the Afternoon (2003), in which an Afghan girl goes to school against the wishes of her family and dreams of becoming the President of Afghanistan one day, also became famous. The film's name is derived from the title of a poem by the famous Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca.

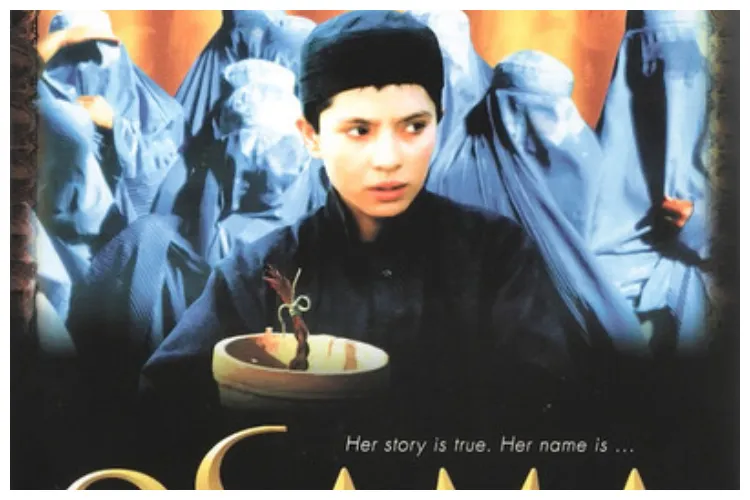

Beyond these references, if any Afghan film showed the reality of that country, it is Siddiq Burmak's Osama (2003). The film not only won awards at many film festivals around the world, including the Cannes Film Festival but also did a business of $3.9 million. The next year came Atiq Rahimi's Earth and Ashes (Khakestar-o-Khak, 2004) which had its world premiere in the Uncertain Regard section of the 57th Cannes Film Festival.

A Poster of the film Osama

A Poster of the film Osama

The next film to get worldwide attention was Gol Chehre (2011) by Iranian filmmaker Wahid Moussa.

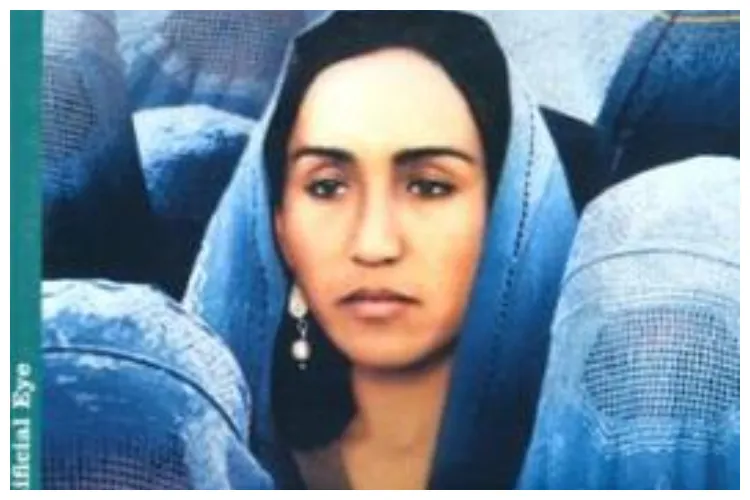

At this time, Afghanistan remains in news headlines due to the withdrawal of American and Allied forces and its occupation by the Taliban. The Taliban have almost destroyed the Afghan film industry. It is surprising to see that most of the films made in Afghanistan are cinematic resistance to Talibani radical Islamic ideas. Siddiq Burmak's film Osama is the story of a 13-year-old girl (Marina Golbhari) under the Taliban regime who works as a boy to support her family and takes her new name - Osama.

There is no man left in his family. She works with her mother in a hospital that was shut down by the Taliban and women were prohibited from leaving their homes for work. When they caught the boys and started sending them to Islamic training camps, one day Osama is also caught. She is caught as her periods came while she was in the camp. The Taliban hang her upside down in a cold well. She is eventually forced into a marriage with an old man. In the last scene, we see the old man taking a bath in a tank full of hot water. Steam is rising from the water of the tank and Osama, who is imprisoned nearby, is sobbing and shivering in fear. This film is an apt description of what the Taliban regime will be like for women and others.

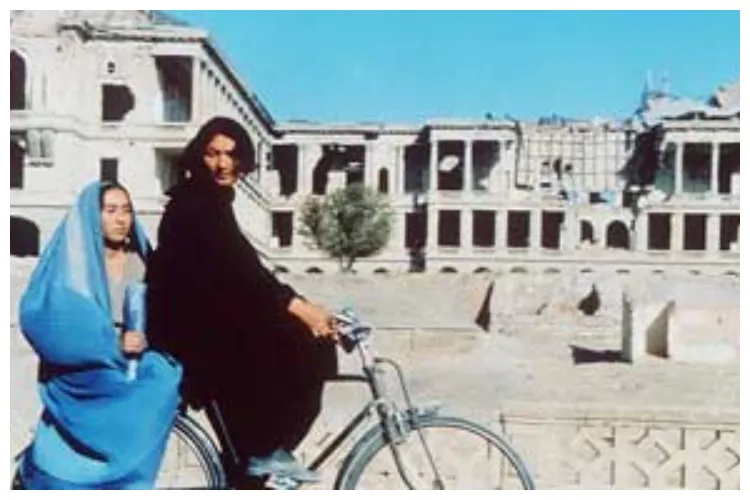

A scene from the movie Gole Chehra

Wahid Moussen's Gol Chehre (2011) is based on a true incident in which people risk their lives to save prints of many rare films from a Taliban attack. Ashraf Khan, an avid cinema lover, used to run a cinema hall called Gol Chehra that was burnt down and destroyed by the Taliban. They want to rehabilitate this cinema hall. With the help of the director of the Afghan Film Archives, he goes to Iran and finds a person who can set up a projector to show films. The inauguration of the Cinema hall Gole Chehre is being done by showing Satyajit Ray's film Shatranj Ke Khiladi.

As soon as the show starts, the Taliban blow up the cinema hall. They kill Ashraf Khan, issue a fatwa to burn all the films of the film archive. Dr Rukhsara, a widow working in the Red Cross Hospital, plans to save rare films from the archive.

Rukhsara does not lose courage even in the dreadful moments of the Talibani era. After the Taliban are wiped out by US forces, Rukhsara, with the help of an Iranian cinematographer and director of the Afghan Film Archive, rebuilds the Gole Chehre Cinema Hall opens it with a screening of Shatranj Ke Khiladi. This film also depicts the craze for Indian films in Afghanistan.

The story of Osama - a scene from the film

Atiq Rahimi's film Earth and Ashs' (2004), originally titled Khakestar-o Khaq, should also be noted for Abdul Ghani's fine performance in the role of an old man. An old Dastgir sits on the side of the road with his grandson Yasin during a long journey in a US bombing-ravaged Afghanistan. This dusty gray road leads to the coal mine where Dastagir's son works. Old Dastgir has to reach out to his son and inform him that his village and family have been destroyed in the bombing.

Their journey is full of difficulties. He is caught between unbearable loneliness and his self-esteem. He encounters a variety of people, including a deranged watchman, a philosophical shopkeeper, a mysterious woman waiting endlessly for someone close to her, and people devastated by this meaningless war that seems to be going nowhere. Frost causes pain during the night. The old man spends the night burning the wooden horsecart to escape the frost and the next morning he walks with his grandson on horseback.

Also Read: UNESCO protected Kuthound Ramleela is rooted in inclusiveness

The film is a cinematic attempt to find humanity in the devastation caused by the war going on in Afghanistan. The bridges, houses, roads, and mountains, damaged by the U.S. bombing of Afghanistan, have been used in the film like a moving landscape. The eyes of the old protagonist Dastagir, tell the past without saying anything while the future of the country can be seen in the eyes of his grandson Yasin. The real strength of the film is the adaptation of the metaphor of the eyes of a grandfather and grandson.

At this point, the Taliban rule Afghanistan, again and this will mean the extinction of art, literature, cinema and secular culture is very close.

(Ajit Rai is a veteran Film reviewer)