.webp)

Aasha Khosa/New Delhi

The only reason why V J Thomas, a young man in his late twenties employed in Ahmedabad, had appeared for a written test for the job of Administrative Assistant in the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) at Trivandrum in May 1972 was he wanted to return to his native state. Finally, one day when he was interviewed for 45 minutes as against 10-15 minutes given to other candidates, he noticed one engineer on the interview board was asking him pointed questions.

Little did he know that the engineer who was grilling him would become his boss, hero and idol, and the President of India in that order.

“Thomas, do this and finish it by …pm on this day,” is what the young engineer A P J Abdul Kalam would tell his office assistant in the coming months. “Initially, he would ask me 'Can you do this and that and when I delivered in time, he started calling me by my name and giving me precise orders.”

Thomas, who took voluntary retirement from ISRO in 2000 and now lives in Thiruvanthapuram, said back then the government organizations were not as dynamic as they are today. “There was inertia, cynicism, and negativity all around; it’s amidst this that I found how dedicated he was and how he never allowed the acidic environment around to overwhelm him,” Thomas says.

Kalam being a workaholic was something many of his peers and juniors didn’t like about him back then. Thomas told Awaz-the Voice that Abdul Kalam was working on a project on the use of fiberglass in the spacecraft when he had joined him as an administrative assistant. He moved around in the office and went to others’ desks to check on their work.

V.J Thomas

“People thought he was eccentric and a simpleton. Since I worked with him, I knew he was a very smart boss and a great manager of men,” Thomas said.

His style of working was very different. He would allot work and instinctively know who was lagging. “He would go to the person’s desk and ask him how much progress he has made,” Thomas said.

Realizing that the person was not doing enough he would never shout at or scold him. “I have never heard him say what is this or what nonsense is that to others,” said Thomas.

Thomas remembers Kalam as a “polite, humane and yet a firm boss, who understood human mind like no one else.”

“He was a great motivator and knew how to make others work,” Thomas said. He would sit with a reluctant person and tell them, “Let us do it together; let’s check where the problem is?” There was no way to escape his charm and politeness. “With his persuasive style, people would finish work in time”

Giving an instance of Kalam’s working style, Thomas said, he would always finish the big tasks one or two days in advance of the event. He would ensure all members of the team did the same. He would declare: The two days are for all to feel refreshed and relaxed.

One day, at midnight Kalam, appeared in the hall where we all were working for the event and declared, “Now you need to take a break; I will attend to my office; check my mail and office work and will be ready and in office by 6.30 in the morning.” His only demand to Thomas was to leave a driver who had taken a good sleep with him. “There was no way we too wouldn’t reach the office by 6.30 am,” he said. Thomas later learned that he was in the office till 2 pm.

Thomas had to pick him up once from his lodge where he stayed in Trivandrum. He had reached 5 minutes earlier not knowing Kalam’s habit of being ready at the precise time.

He ushered Thomas to his room while he went in to get ready.

“His bed, table, and floor mat had stacks of books. The hay mat traditionally used in Kerala looked like a cradle with a boundary made of columns of books.” The room was very neat. Thomas was so impressed by his boss that he became his ardent admirer and hero-worshipped him all his life.

“He is my hero and I say proudly that people wouldn’t believe such a human being ever walked on this earth,” Thomas, who is undergoing cataract surgery and therefore couldn’t provide his pictures, said.

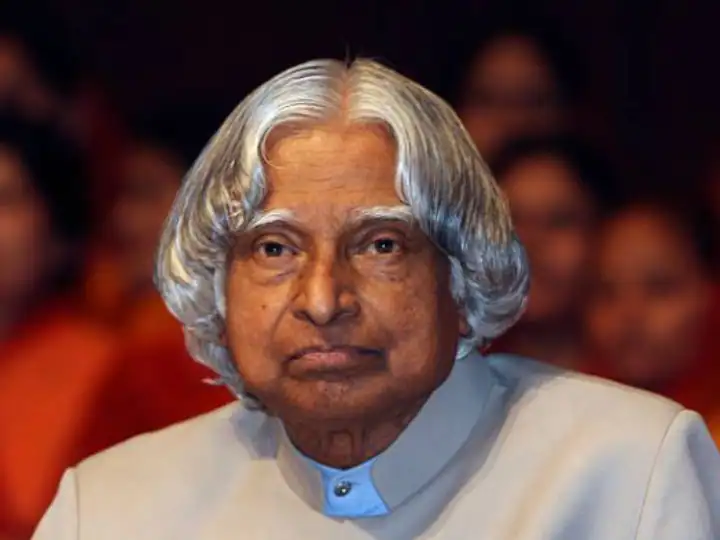

APJ Abdul Kalam

Kalam had to face a lot of snide remarks and criticism after the failure of the first ASLV satellite in 1979. However, when the satellite was launched successfully a year later with indigenous technology and efforts, Thomas says many of his colleagues thought Kalam was getting undue praises in the media.

I know the man was not after money or fame; he had no plans for the rise in his career that he eventually had; he just wanted to do something for the nation and his mantra was go indigenous,” reminisces Thomas.

Another criticism that Kalam received at his workplace which Thomas was privy to was he did not have a doctorate. “Today he has 30 honorary doctorates from so many universities,” says Thomas who kept tabs on his hero.

Later when he read Kalam’s book Wings of Fire Thomas found his hero had lived up to his expectations of not nurturing any bitterness about those days. “He has merely written he failed to understand why some people feel jealous when great things are happening to the nation.” Thomas worked directly under Kalam for five years and later when he moved to DRDO, he kept visiting Thumba (ISRO station) as an ex-officio director of the project. “Whenever I met him, he would place his hands on my shoulder and speak affectionately.”

Thomas was livid to read the Malayalam translation of Wings of Fire as he found inaccuracies in the book. He met the owner of DC books who hails from his village Kanjirapally in Kottayam and made him change the text. “The next edition of the book had a deadline and Ravi (DC Books owner) told me that I have five days to work on the book and I did it.”

He was so happy to do it.