Saquib Salim

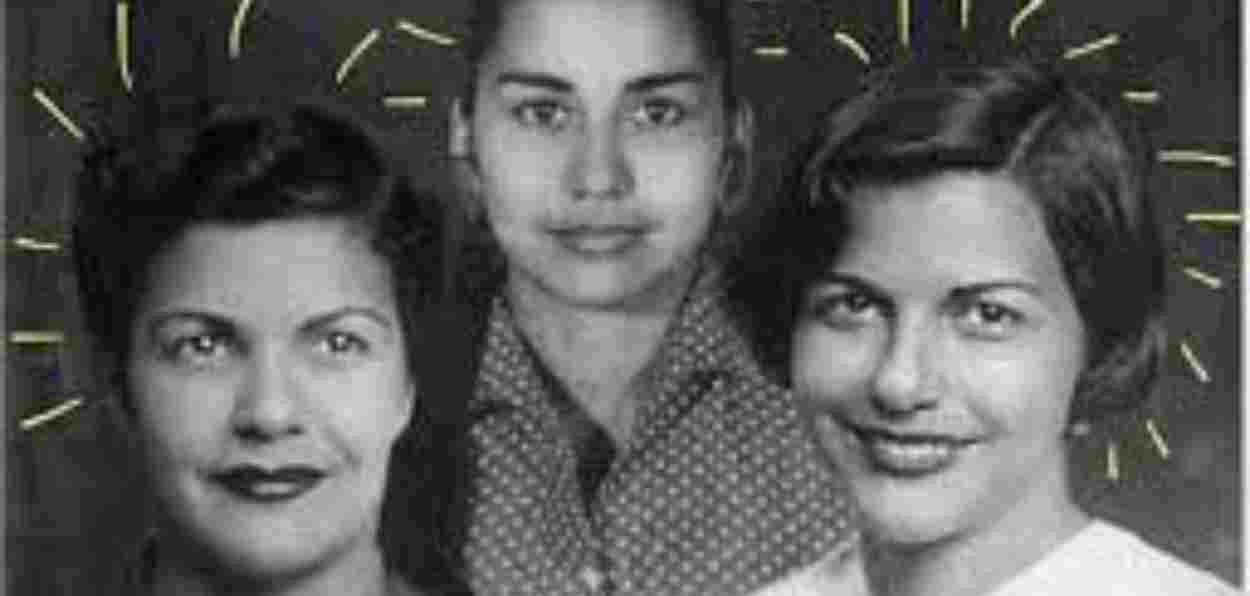

The Mirabal sisters – Patria, Minerva and Maria Teresa – of the Dominican republic were revolutionaries who opposed the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo. They were assassinated by the regime on 25 November 1960.

Minerva was the one who had the most active role in politics. She founded the Revolutionary Movement together with her husband Manolo tavarez Justo. Maria Teresa also became involved in the Movement. The older sister, Patria gave her house to store weapons and tools for the insurgents. They are considered heroines for the Dominican Republic. Their remains rest in a mausoleum that was declared an extension of the National Pantheon, and is located in the Hermanas Mirabal House-Museum, the last residence of the sisters.

There was no internet in 1981 when Women Rights Activists started observing 25 November as a day against gender-based violence in honour of the Mirabal Sisters and the United Nations (UN) designated this date as the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women in 1999.

The original resolution adopted by the General Assembly of the UN in February 2000, did acknowledge, that “the term ‘violence against women’ means any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life” but at that time idea of cyber crimes was not yet a threat.

More than two decades later, cyber crime has emerged as one of the gravest threats to women in India and elsewhere. Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools like Deepfake are being used to morph the videos and images of celebrity women, issuing online rape threats to women journalists, apps to virtually ‘sale’ women online, fake profiles, and much more.

The UN, now, acknowledges ‘a high prevalence rate’ of technology-facilitated violence against women and girls across the globe. According to the UN, “a global survey showed that 73 percent of women journalists have experienced online violence. Twenty percent said they had been attacked or abused offline in connection with online violence they had experienced.” About the women politicians, the report notes, “women cited social media as the main channel of this type (gendered psychological) of violence, and nearly half (44 percent) reported receiving death, rape, assault, or abduction threats towards them or their families.”

Several researchers have pointed out that the emergence of social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Twitter (now X), etc. has created new problems for women. Men hiding behind anonymous profiles using cyber tools stalk, threaten, or defame women. This may impact the sexual, physiological, or psychological well-being of victims. Social defamation might hamper the career and personal relationship prospects of a woman as well.

Sahana Sarkar and Benson Rajan interviewed 30 Indian women survivours of online violence. They show cyber violence as an extension of physical violence against women. One of the survivours said, “I started getting emails describing how I was looking in the morning on my way to the office. They were never exact descriptions of what I was wearing, so I ignored assuming this was some prank. Then gradually the emails became very sexual explaining in graphic detail how he wanted to have sex with me. I got very annoyed and disgusted and put that email in spam. For the next three months, it kept coming in spam and I did not notice. But I wish I filed a complaint earlier than probably I would not have gotten raped.”

Sarkar and Rajan write, “In 25 out of 30 cases of cyber violence within the sample, violation online extended to physical harm. Having said that, the researchers acknowledge that sometimes cyber violence can also be an extension of physical violence. It is very evident from the narratives of the cyber violence survivors that physical violence against women and cyber violence against women feed into each other.”

In the year 2021, according to the National Crime Records Bureau, 4,555 cyber crime cases were filed in India which had sexual exploitation as a motive. It must be kept in mind that crime against women in India always has low reporting because of societal pressures working against women.

In the same year, 1852 persons were arrested for Identity Theft (which includes fake profiles), 4819 people for Publication/transmission of obscene / sexually explicit acts in electronic form, 2071 for Publishing or transmitting obscene material in Electronic Form, 1366 for Publishing or transmitting of material containing sexually explicit act in electronic form, 689 for Publishing or transmitting of material depicting children in the Sexually explicit act in electronic form. However, the conviction in respective charges remained low. The conviction was 61 out of 1852, 139 out of 4819, 86 out of 2071, 21 out of 1366, and 7 out of 689 respectively in each category of crime mentioned.

ALSO READ: British bombed civilians during the Quit India Movement

The technology is being used to silence and marginalize women. It has given a new weapon to misogynist violent men who want to control the sexual, social, and economic behaviour of women. The novelty of the method makes it difficult for civil society and law enforcement agencies to appreciate the threat of online sexual abuse at a par with physical sexual abuse. In a world where economy, education, information, social interactions, etc. have shifted to cyberspace online sexual violence attempts to push women out of the mainstream. Sadly, researchers show that women, most of the time, withdraw themselves silently from social media spaces as a result of such threats.