Shekhar Iyer

As India completes 75 years since attaining Independence, one does wonder what has made difference to our political system all these years. Is it the conduct of our political parties for the good and bad in the cause of the people or the work of prime ministers who evolved as leaders from their beginnings in these parties?

As they say, circumstances make men but men also create circumstances that evolve to respond to the demands of societies. So have our political leaders.

75 Years of Independence

Their story is also the story of the people's search from the basic requirements of life to seek avenues for their aspirations. Those leaders who responded to the calls of their time and did what they could left legacies and memories that are cherished to this day.

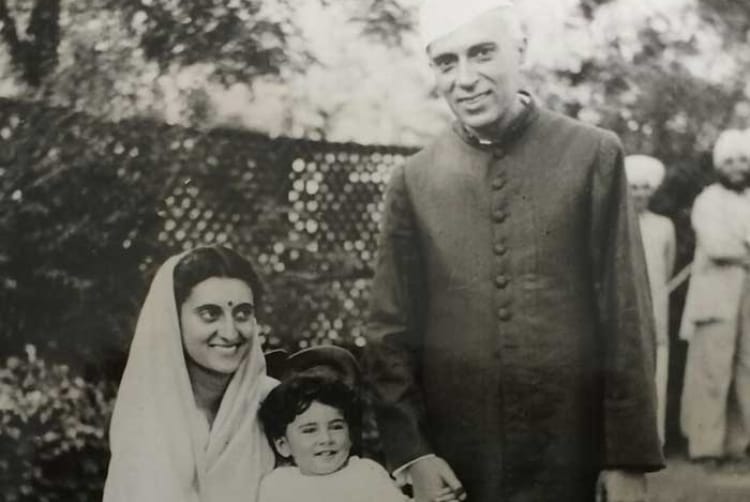

Jawarharlal Nehru, who was our first prime minister as desired by Mahatma Gandhi, ruled for 17 years from 1947 to 64. He faced enormous challenges managing the travails of a nascent nation that had to recover from the deep pain on its masses caused by the Partition.

Caught between the meager resources left behind by the outgoing rulers and the anguish of the hungry millions, Nehru introduced a model of governance that sought to nourish India's parliamentary democracy. In his vision, it was to be through a mixed economy, modern agriculture, spread of science and technology, and essential infrastructure.

Nehru was guided by what his admirers saw as a statesman-like approach as he responded in his way to a world that too was recovering from the Second World War.

As he battled the scars of the Partition, Nehru tried to enlarge our understanding of secularism in the hope it would help Indians overcome their sense of deprivation and alienation between and among the communities.

But secularism as a political concept has remained confusing to the people even to this day with various interpretations even though they have inherited tradition that has respected all faiths. But as a political statement, it was a tool of which they had little understanding -- as subsequent times showed.

Despite the advantage enjoyed by luminaries and talents that embellished his government, Nehru's personality and orientation shaped major decisions, which to this day are either praised or criticized by admirers and critics alike.

After him, Lal Bahadur Shastri was in office only for 18 months before he passed away in far away Tashkent in 1966. But in his rather brief tenure, he managed to show what a non-Nehru family leader could do.

A down-to-earth leader whose understanding of the rural poor seemed wider than his aristocratic predecessor, Shastri brought to his office a deeper knowledge of governance. He had served as minister for external affairs, home, and railways before the death of Nehru, which catapulted him into the hot seat.

Shastri focused on improving India's agriculture, ushered in the green and white revolutions, and laid the foundation for the country to emerge as one of the major food grain producers to meet the world's hunger. His biggest challenge came in the shape of the India-Pakistan War in 1965, which ended with the Tashkent Agreement. But the stress caused by the war, perhaps, also claimed his life.

Shastri's sudden demise saw the first of India's intense rivalries within the ruling Congress party. As Indira Gandhi was seen by Nehru's loyalists as a person whose time had come to occupy the post of PM, the old guards who constituted the Syndicate were not reconciled to a younger woman taking up the mantle. She was just 49.

Her advantage lay in not being just Nehru's daughter but one of his key unofficial aides who saw many things at close quarters and one who worked closely with him during his premiership for most of his tenure. She was elected by the party to succeed Shastri while seniors like Morarji Desai. Congress president K Kamaraj was credited for her ascension to the top post.

A person with her mind, Indira Gandhi wanted to break away from the Congress Syndicate and looked for opportunities to dispel the impression she was a weakling who would do their bidding. But her style brought her admirers and friends but also enemies--not just political rivals.

She utilized the opportunity provided by the untimely demise of President Zakir Husain in 1969, which set off a chain of events when the Presidential election was held to choose Husain's successor. She challenged the Congress Syndicate that preferred Neelam Sanjeeva Reddy. She suspected that the Syndicate was keen to foist a "difficult" president like Reddy over her to curb her style of working as PM.

She preferred V V Giri, who was India's third Vice President and acting President following Husain's death, to succeed him.

She got Giri to resign as acting President to contest as an independent. She ensured his victory over Reddy by 15,000 votes in the election. A livid Congress Syndicate expelled her from the party.

It was the first time a PM had been expelled from her party. However, she formed her party and went on to dominate national politics until she was unseated as an MP for electoral malpractice by a court verdict in 1975. In response, she clamped the Emergency to curb opposition against her. She abolished privy purses, nationalized coal, banks, and the insurance sector, and won the 1971 elections on the back of the slogan, "Garibi hatao" which was in response to the opposition's "Indira hatao."

She created Bangladesh splitting Pakistan in 1971 and conducted the first nuclear test in 1974 daring big powers. Her reign lasted till 1977 in the first phase.

This was the most tumultuous phase of politics that saw mass movement against corruption led by J P Narayan.

In 1977 when she called the elections in the hope to do away with the tag of "dictator," the Congress lost the Lok Sabha polls very badly. She was drowned in the huge tsunami of widespread discontent and all non-Congress parties were cobbled up by the first non-Congress government of India.

The 1977 elections gave rise to the prime ministership of Morarji Desai. A Gandhian to the core, Morarji Desai was Indira Gandhi's staunch rival in the good old Congress party. But Desai and his Janata Party colleagues who included former Swantara Party leaders, Socialists, and Jana Sangh leaders in a kichidi arrangement could not stick together for too long.

The intentions of the Janata Party government were laudable but delivery on many fronts left the arrangement in tatters. The Socialists resented the Jana Sangh leaders like Atal Bihar Vajpayee, accusing them of being dual members -- of the RSS as well as the Janata Party.

Indira Gandhi had the last laugh when she lured Charan Singh away from the non-Congress combination against her by dangling the post of the PM. Though a Kisan leader with earthly concerns, an ambitious Charan Singh fell for the bait and held that post for less than a year till she pulled the rug under his feet in 24 weeks. She returned to power again in 1980 and lasted in office till her assassination in 1984.

As Prime Minister Narendra Modi spoke from the Red Fort in his address on August 14, 2014, "today if we have reached here after independence, it is because of the contribution of all the Prime Ministers, all the governments and even the governments of all the States. I want to express my feelings of respect and gratitude to all those previous governments and ex-Prime Ministers who have endeavored to take our present-day India to such heights and who have added to the country's glory."