Ahmed Ali Fayyaz/Srinagar

Signage of Muzaffarabad, Islamabad, and Rawalpindi appeared on the streets across Kashmir in the decade of the late nineties when under Confidence Building regimes undertaken by India and Pakistan, two cross-LOC routes between Srinagar and the occupied territory served the limited purpose of a passenger bus service and barter trade was also started between two 'Kashmirs'.

Years later, authorities began noticing that even some consignments of drugs and arms were flowing into the Kashmir Valley through the same route. Both were terminated.

Ironically in just 10 years the ‘changing of heart’ began getting an endorsement from New Delhi: Kashmir’s mainstream politicians, administered by powers in the Union Capital, launched a competitive campaign of showing the Kashmiris ‘the Road to Pakistan’.

Tourists visiting the now closed Aman Setu at Kaman Post, Uri, Baramulla

It was only a minuscule smuggling of the contraband. But far more than material, it carried a potentially dangerous symbolism. Many in Kashmir began feeling that they were part of Pakistan’s politics, culture, religion, and language. They began thinking that their association and love for an Islamist Pakistan were ‘normal’ and Kashmir’s separation from the Union of India was ‘just a matter of time’.

Years later, the street turbulences of 2008, 2010, and 2016 were arguably a consequence of this “normalization of the direction toward Pakistan”.

The direction towards Delhi remained materially and psychologically blocked. The chasm was permitted to widen not only between Srinagar and Delhi but also between the Muslim-dominated Kashmir and the Hindu-dominated Jammu. A 300-km long fair-weather conventional highway used to remain closed for traffic for weeks together at the drop of rain’. It was the only lifeline for the valley’s population of 5-6 million people through surface communication.

For the rich, there was another lifeline, though—the air service in the Srinagar-Jammu-Delhi sector. Even this remained disrupted due to bad weather, fog, and poor visibility, mainly due to snowfall in winter.

Bus running between Seinagar and Muzafarrabad

Bus running between Seinagar and Muzafarrabad

The result was Kashmir remained cut off from Jammu, from the rest of India, and the rest of the world for weeks every year. The absence of physical integration sustained and aggravated political and psychological alienation among several generations.

Thereafter, one day New Delhi realised that the Kashmiris’ political, psychological, cultural, and educational integration with the rest of the country was not possible without showing them the smooth better road to Delhi, without giving them freedom from their toughest journey to Jammu and onwards.

Twenty years later, the upgraded and modernized airport at Srinagar is now handling 100-120 incoming and outgoing flights seven days a week. But most of the travelers benefitting from this luxury belong to the affluent and the upper middle class as the Srinagar-Delhi tickets are often incredibly expensive.

An ambitious project of developing the conventional Srinagar-Jammu highway, which was created and opened as the Banihal Cart Road by the Maharaja in 1922, into a four-lane modern highway started in 2009. 15 years on, it is nearing completion and likely to be dedicated to the nation by the Prime Minister in February 2024.

Salamabad Trade fecilitation center

Salamabad Trade fecilitation center

The project includes the construction of 12 tunnels. The Indian highways’ two longest tunnels—the one-tube, two-lane Syama Prasad Mukherjee tunnel between Nashri and Chennai (9.28 km) and the two-tube, four-lane Navyug tunnel between Qazigund and Banihal (8.45 km), both already completed and operational, are on this highway.

Authorities are hopeful of completing the ongoing works on the most challenging Banihal-Nashri part, including 4 tunnels, in the next three months. This highway between Srinagar and Jammu is reducing the distance from 294 to just 240 km. Until 2012, when the Jammu-Udhampur part was completed, it was a journey of 12-14 hours by car. In case of inclement weather or a blockade caused by a road accident, entire traffic would get stranded and it would stretch out to 18-30 hours, even more. Currently, it stands reduced to 5-6 hours.

Officials of the National Highway Authority of India insist that after completion of all the ongoing works, the travel time between Srinagar and Jammu would further come down to just 4-5 hours.

The ultimate game changer will be the operationalization of the rail link between Srinagar and Jammu which, according to well-placed officials, will be inaugurated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Union Railway Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw towards the end of February 2024.

“The ultimate deadline of February 2024 has been set for both the highway and the railway line. It has been made clear to everybody that these major projects of national importance shall have to be inaugurated before the Lok Sabha elections of 2024 for which the process would start in March. Currently, these are the projects of the top-most priority in the UT”, said a senior Government official.

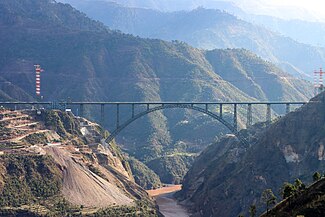

The Bakal Railway bridge

The Bakal Railway bridge

Completely cut off from the British Indian railway network, Jammu was connected through Sialkot (now in Pakistan’s Punjab) with the completion of a 40-45 km track in 1897. In 1902, the British engineers submitted a proposal of connecting Jammu to Srinagar over the west of the Pir Panjal mountain through the historic Mughal Road. In 1905, Maharaja approved a narrow gauge (30-inch) track via Reasi.

ALSO READ: J&K Assembly nominations bill seeks to undo Kashmiri Pandits' exclusion from political process

Around a hundred years later, the Indian Railways started laying a broad gauge track in the valley plains from Qazigund to Baramulla. In 2002, the proposed Jammu-Srinagar Railway Line was declared as a project of national importance. Twenty-two years later, this historic rail connectivity is becoming a reality—for the first time linking Srinagar and other valley towns to Jammu, Delhi, and the ultimate inland destination of Kanyakumari.