Saquib Salim

Saquib Salim

The caste system among Indian Muslims is often debated among academic circles and hushed elsewhere. Many, especially the upper caste people, believe that it is an invention of modern politicians while others blame the high-brow academia for exaggerating it.

Whenever I tried to broach this subject, I come across two opposite reactions; either people accuse me of being an upper-caste Muslim trying to silence the lower caste and others, for some strange reason, think that my JNU stint as a student makes me think along these lines.

My introduction to the caste system among Muslims and the silencing, exclusion, and discrimination practiced against the lower caste for centuries were not taught to me by any scholar of the modern English education system. Mohammad Hashim, my paternal grandfather, Abbaji to me, an Islamic scholar, was the one who introduced me to this dark reality.

I belong to the Gara community, a local caste found in Muzaffarnagar, Saharanpur, and Haridwar districts of Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand. Traditionally, these caste people were agriculturists and land owners. Socially they were at par with the Jats of the area. Though economically well-off during the early 20th century Garas were mostly uneducated.

Abbaji (grandfather), was born in 1918 and he lived in Dadheru, a village in Muzaffarnagar. Those were the times when social and educational awakening in India was happening and his family did not remain untouched. Under one Hafiz Ameeruddin, Abbaji learned Islamic teachings. Abbaji memorized the Quran in his early teens and he was rated as a bright student.

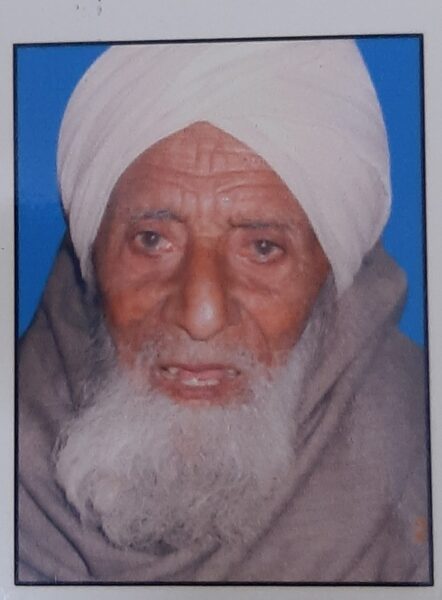

A rare picture of Abbaji, Mohammad Hashim

Among Muslims, there is a practice that the young scholars who have memorized the Quran would lead Taraweeh prayers during Ramazan. Taraweeh is a long Namaz, where one chapter of the Quran is recited each day of Ramazan. Thus, 30 chapters of the Quran are completed in the holy month.

In 1933, his teacher decided that Abbaji should lead the Taraaweeh prayers. Being a bright student he wanted him to recite the Quran in front of the best Islamic scholars. The idea was that his student must also be subjected to constructive criticism.

He ended up learning one of the most important lessons of his life!

In those days, Manglaur, a town near Deoband, was famous for its Islamic scholars. The town has produced many Islamic scholars during the 19th and 20th century. It was here that my grandfather was asked to make his debut.

On the first of Ramazan, a young Hashim (Abbaji) was called upon by Qazi Abdul Ghani, a senior person of the town, and, of course, an upper caste, to lead the prayers. Ghani asked the people present in the mosque to tell the young boy about how much of the Quran they wanted a young Hashim to recite. It was a common practice to get endorsement from public who has gathered there. Someone remarked, “Gare ka ladka hai, kitna hi padh lega. Padhne dijiye.” (He is a Gara boy. How much can he recite? Let him recite.)

This caste slur made by an upper caste man, and endorsed by others present. A young Hashim was introduced to the harsh reality of the caste system. An egalitarian’ space like a mosque was used to play out caste discrimination. If not for his mentors, including an upper-caste gentleman, Abbaji would have succumbed.

Ghani took him to a corner and told him, “Jitni himmat hai utna pehli do rakat me padh dena.” (Recite as much of the Quran in the first two Rakats of the Taraweeh as you can.) An obedient student, Hashim, started reciting with a conviction of proving the casteist slurs wrong. Young Abbaji recited 20 chapters, out of 30, of the Quran during the first two Rakats and completed the whole Quran during the night, the first Taraweeh of his life.

When Taraweeh was completed all but four of the people remained in the mosque.

Muslims offering Namaz

The feat of reciting a whole Quran in one Taraweeh is called Shabeena and is considered an achievement. He became famous as someone who could recite Shabeena at will. Abbaji could shut the mouths of his critics on the very first Taraweeh but the episode made him realize the harsh reality that the mosques are not immune to caste discrimination.

About 70 years down the line, it was the Ramazan of 2002. We were trying to sleep at our home when someone knocked on our door. It was a huge crowd, mostly of upper caste people of a nearby locality, fighting among themselves over an issue of recitation during Taraweeh.

One group, mostly elders, believed that the man reciting was wrong in his recitation scheme while the other, mostly youngsters, were backing the man. So they decided to wake up Abbaji and take his opinion.

Abbaji decided in favour of the man leading the Taraweeh, a decision accepted unanimously. From being rejected as a lower caste boy who should not be taken seriously to being respected as a scholar by the upper caste his journey was not easy.

ALSO READ: Why AIMPLB is responsible for low educational levels of Pasmanda Muslim women’

This is how I learned my first lessons about caste-based discrimination and ideas of social justice.

Saquib Salim is a Delhi-based historian writer. This article is an abridged version of the one that appeared in Heritage Times portal)