When I visited the International Red Cross (ICRC) Museum in Geneve, Switzerland a few years ago, I was shocked to realize that the 1971 war was being projected as a passing memory of incessant tension between India and Pakistan. The trigger- the genocide of 3 million Bengali-speaking people in what was then East Pakistan – didn’t qualify for the list of manmade tragedies. It’s not even mentioned anywhere in the museum. The only clue to it is an artifact made by a Pakistani prisoner of war in India from the golden wrap of the Charminar cigarette pack displayed there!

The museum of the world’s worst human tragedies located on a hillock overlooking the UN Human Rights Council has otherwise a modern and artistically-curated collection. The AI-enabled experience of listening to the poignant stories of the victims of the two world wars, tsunamis, earthquakes, the holocaust, famine, etc. moved me to the core. The final display - iron chains hanging from the roof, swinging constantly and yet never touching each other – is a metaphor for displacement, families getting separated in the man-made calamities. I left the place impressed and yet heavy-hearted.

As children, my generation has painful memories of the war and its context and even half a century later, the world is not even ready to speak about it. The genocide and systematic rapes committed by the professional army of Pakistani state on its people are unparalleled in the history of mankind and yet it’s not even worth a mention in the museum of world history.

Bangali women fighters marching

I vented my disappointment in the feedback note to the Museum Director. I asked him if the genocide of brown people was any less tragic than others. It was a brief note, but today, I am shouting out to the world my experience as a child of those tragic days.

I was nine years old when India and Pakistan went to war. In my school in Reasi town (Today's district headquarters) of Udhampur district in Jammu and Kashmir, we were made to dig trenches in our school grounds that was dotted with mango trees. We also practiced mock drills by rushing inside the L-shaped trench closest to our classroom for the eventuality of a Pakistani plane bombing the area.

One day our Headmistress Mrs. Nanda spoke to us in the morning assembly. She asked each student to make a small donation out of their pocket money for the jawans. I remember Daddy generously giving me Rs 5. Mrs. Nanda frequently addressed us and mostly spoke on how one must love one's country. Senior students were asked to donate blood for soldiers.

Youth of East Pakistan venting their anger on a caricature of Pakistani ruler General Yahya Khan

Youth of East Pakistan venting their anger on a caricature of Pakistani ruler General Yahya Khan

Though the talk of the war had no impact on our lives, the environment was generally gloomy. Children like me didn’t understand the implications of war but the talk among elders at home made me realize something bad was going to happen. One day, the class teacher asked us to be ready to greet soldiers as a fleet of tanks was to pass by the schools. We were trained to say Jai Hind and Bharat Mata ki Jai to them to boost the morale of the soldiers who were heded to the battlefront. More than being excited, I was scared at the prospect of facing a tank. For some reason, the tanks on the way to the battlefield never came.

Manzoor Biwi was a jolly-natured girl in our class. She was poor in English and made fun of the language; stubbornly she never even cared to learn it. However, only after we dug out that L-shaped trench close to our classroom, did I realize she was faint-hearted. Manzoor often spoke of doom. Looking at the sky she predicted a bomb would fall and we will die. One day there was a roar of an airplane flying in the skies. Manzoor screamed and became hysteric. She jumped into the trench and continued calling Khudda for help.

As Pakistan tried to shift the war to J&K by attacking Chamb in Jammu, the war had come closer to us. In the evenings, elders pointed to the crimson horizon and said the sky was coloured because of the war. I failed to make out if the colour was because of the blood of soldiers or the fire opened by the two Armies.

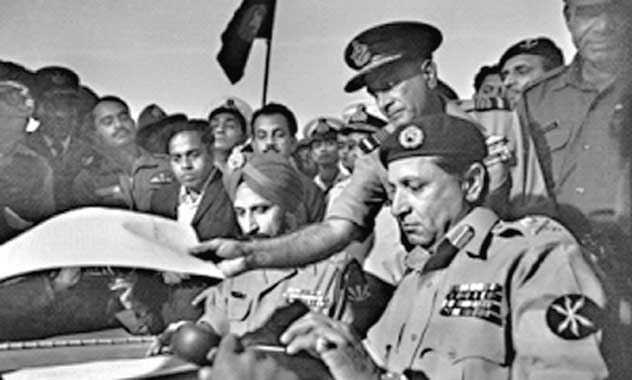

Pakistani commander Lt Gen A K Niazi signing the surrender document in Dhaka

Back then there was no round-the-clock television or social media; All India Radio was the only means of news and information. I listened to the news on the transistor. The scene of the war theatre was beyond a child’s comprehension but the run-up to it was quite disturbing. The AIR broadcast programs on Bangla refugees in India. Some 20 million of them had escaped violence unleashed by the Pakistani army and come to India.

Children of my generation had no idea of rape or sexual assault, yet from the radio programme, I knew something terrible had happened to women there. The images of skinny Bangalis living in camps in India in newspapers shocked me. I often cried in the evenings thinking of those people and wondering if it happens to all humans. I stopped going out to play with friends.

Life would come to a standstill by the evening; the power supply was off and we had to observe a “blackout.” This was to camouflage our cities and towns against the Pakistani military planes bombing us. This meant candlelight dinners for my family. One day I asked Daddy what was all this about. I remember he had just finished eating meals; he drew maps on the thali to explain how the two territories of Pakistan were on either side of India. Daddy also explained to me how Pakistani rulers didn’t like Bengalis. This gave me some clarity on what was happening.

Listening to Pakistani Radio that spewed propaganda was forbidden.

One day, a drummer went around the town of Reasi asking women to come to the Townhall as the District Collector would meet them. I got my mother’s permission to go there with our landlord's wife Mrs. Arora. My mother, a devoted Kashmiri homemaker, was not interested. The town hall was located on the edge of a big pond in the middle of the town where we watched Ramlila show in autumn. We, the children, frequented the Shiva temple on its periphery for prayers on exam days and picked a few leaves of Tulsi to keep in our mouths for luck.

The author at the ICRC museum in Geneve, Switzerland

Sushma Choudhary, the first women IAS officer from J&K was dressed in a sari; she had no makeup on her face and yet looked radiant and had a commanding personality. She spoke to women about the impending war. She asked them to knit sweaters for faujis and be ready to prepare food at short notice. I am sure I missed many other instructions she gave to the women.

Later in the winter, I remember the whole town erupting in joy and dancing to drumbeats as India had won the war. Pakistan had suffered a humiliating defeat with its Army surrendering before Lt Gen J S Aroura; Bangladesh was now a free nation. Now onwards, I was listening to the AIR programme on Pakistani POWs - 90,000 plus - in which they gave a message about their welfare to their families in Pakistan.

One day, our Hindi teacher Geeta Sharma asked us to write an essay on Independence Day. I wrote it extempore and described the liberation of Bangladesh and the war; the candlelight conversations with Daddy helped me. Geeta ma’am appreciated my essay and showed it to the Headmistress Mrs. Nanda.

I was happy each time a Pakistani POW told his family he was fine and being treated well. For years the trench close to our classroom was never filled with soil again, probably, it was left as a reminder of the war and traumatic times.

ALSO READ: India fought for freedom of Bangladesh as world didn't care

As an adult, I feel that had the world acknowledged Pakistan’s atrocities on its people and held it accountable, the country would not dare to unleash terrorism in Jammu and Kashmir later.