Saquib Salim

“I come here because honestly I feel that by my coming, I may not perhaps do much good to you — but I think that I do good to others, who are not here. That is to say that I make many other people in India, who may not be interested in science think of it, and that is I think a worthwhile task.”

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru said this in his address to the 45th Indian Science Congress in Chennai on 6 January 1958.

After India gained independence in 1947, one of the biggest challenges she faced was to come out of poverty and feed her large population. Its first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, believed “that the economic salvation of India’s millions lay in the development of science and its application to resolve the problems of ignorance, hunger, poverty and unemployment.” It's no exaggeration to say that he led India towards scientific and technological development after a long colonial rule.

In 1947, when he became the Prime Minister the budget for scientific research was 24 million Rupees which rose to 550 million at the time of his death in 964. During this period several institutions were opened, fellowships awarded, and policies made which laid the foundation for a future scientific development of India.

Nehru’s interest in science can be traced back to his college days in England. He studied science only to become a lawyer and a politician later on. He summed up the reason at the Indian Science Congress Session in 1938. He said, “Though I have long been a slave driven in the chariot of Indian politics, with little leisure for other thoughts, my mind has often wandered to the days when as a student I haunted the laboratories of that home of science, Cambridge. And though circumstances made me part company with science, my thoughts turned to it with longing. In later years, through devious processes, I arrived again at science, when I realized that science was not only a pleasant diversion and abstraction, but was of the very texture of life, without which our modern world would vanish.

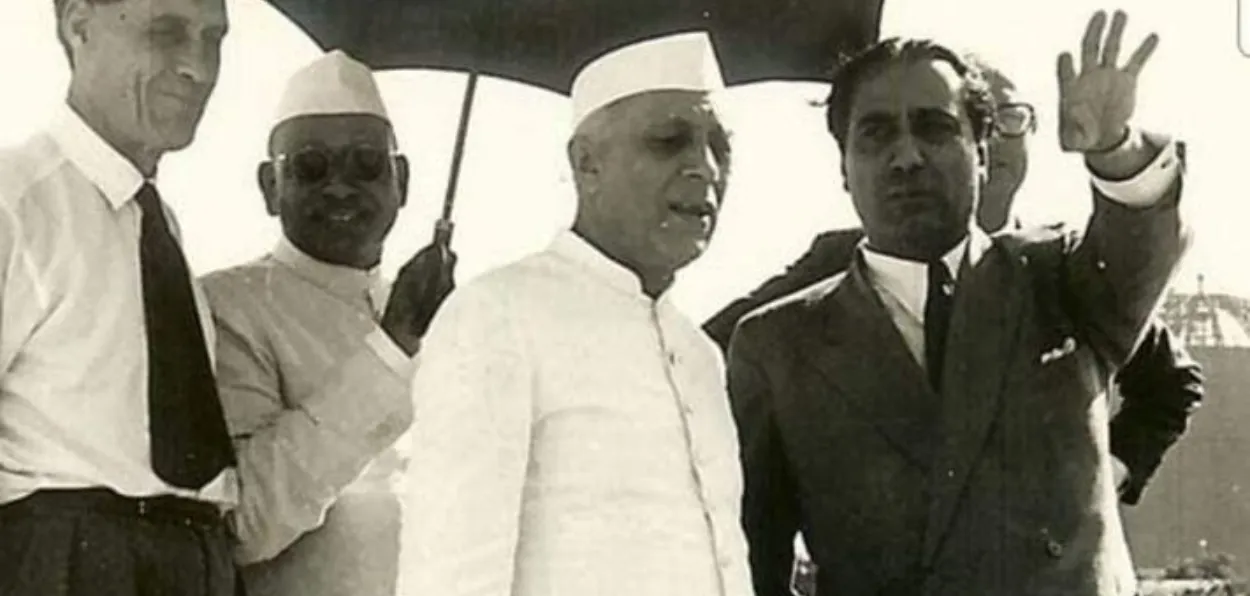

Jawaharlal Nehru with his grandson Rajiv Gandhi

"Politics led me to economics and inevitably to science and the scientific approach to all our problems and to life itself. It was science alone that could solve these problems of hunger and poverty, of insanitation and illiteracy, of superstition and deadening custom and tradition, of vast resources running to waste, of a rich country inhabited by starving people.”

What was Nehru doing at the Indian Science Congress? He was the Chairman of the National Planning Committee of the Indian National Congress. Prof. Meghnad Saha, along with other Indian scientists, wanted to apply science and technology for national development. He has been writing articles and forming public opinion since at least 1934. Baldev Singh writes, “In 1938 when Subhas Bose became President of the Indian National Congress, Prof. Saha persuaded him to set up the National Planning Committee and insisted on a national leader of stature being its Chairman that was Jawaharlal Nehru. Prof. Saha was a member of the National Planning Committee and Chairman of two of the sub-committees. Some differences surfaced due to Prof. Saha’s misapprehension regarding the position of the Congress and Jawaharlal Nehru on the role of large-scale basic and heavy industry. Jawaharlal Nehru was “personally a believer in the development of large-scale industries.”

So, Nehru interacted with the Indian scientists and formulated a national development scheme. In 1937, he declared, “I am entirely in favour of a State organization of research. I would also like the State to send out promising Indian students in large numbers to foreign countries for scientific and technical training, for we have to build India on a scientific foundation, develop her industries, change the feudal character of her land system, and bring her agriculture in line with modern methods, develop social services which she lacks so utterly today, and to do so many other things that shout out to be done. For all this, we require trained personnel.”

The Prime Minister of India was a permanent feature at every session of the Indian Science Congress from 1947 till his death except in 1948 and 1961. In his own words, he attended the Congress to popularise science. Of course, the presence of the PM guaranteed more press coverage and attention of officials.

Nehru pointed out why he attended the Science Congress in his address in 1958. He said, “Every year I appear on the scene. I am invited by the Science Congress authorities. It has become some kind of routine or habit for them to invite and for me to accept their invitation…. It is not quite clear what precise function I perform except, I hope, to try and cheer you up a little and to indicate that the Government which I represent is favourably inclined to science and scientists. Perhaps, that is the principal virtue that I possess in this gathering.”

A similar message was given by Nehru at the 1952 session of the Science Congress at Kolkata. He said, “I come here realizing that I don’t throw any particular light on situations that you might have to consider. Nevertheless, I come here, partly because it satisfies me and I am interested in the development of science in India. I wish to give you, convey to you, well, their sympathy, their message of encouragement, and their faith in the future of science in India.”

This was no mere lip service. Nehru proved his point by encouraging and completely backing H. J. Bhabha, Shanti Swaroop Bhatnagar, and several others. It was not a one-sided love. Indian scientists loved him too.

In 1943, Nehru was elected as the President of the Indian Science Congress. For him, it was a huge responsibility to speak among scientists. In a letter to Indira Gandhi (dated: 15 October 1942), he wrote, ““I am trying to get some more books on science to qualify myself to some extent at least for the presidentship of the All India Science Congress which holds its next session at Lucknow (it was Calcutta - ed.) next January! Not that there is the slightest chance of my presiding over it.”

Nehru was not wrong. He could not attend the session. The colonial British government put him in jail for leading the Quit India Movement. At Kolkata in 1952, Nehru said, “I remember on the last occasion, when I should have attended a session of the Science Congress in Calcutta and when I did not do so, though the failure to do so, was not, well, due to any lapse on my particular part.”

This shows that while on the one hand, Nehru was committed to promoting science and technology in India, on the other scientists were also committed to Indian nationalism. They were working with the freedom fighters and not for the jobs of the British Empire.

In the age of extensive misinformation on social media, we often see charges being leveled against Nehru that he was against the development of arms, especially nuclear weaponry. People forget that Nehru gave a free hand to Homi Jehangir Bhabha in nuclear research. He publicly declared that India should have a nuclear weapon.

Jawaharlal Nehru with school Children

On 25 August 1945, at a press conference when asked if India would try to have an atomic bomb in the future, Nehru replied, “So long as the world is constituted as it is, every country will have to devise and use the latest scientific methods for its protection. I have no doubt India will develop its scientific research and hope Indian scientists will use the atomic force for constructive purposes. But if India is threatened, it will inevitably try to defend itself by all means at its disposal. I hope India, in common with other countries, will prevent atomic bombs from being used.”

When it came to science, Nehru mostly took the backseat and let the scientist steal the show. In 1951 he told a gathering of scientists at Bangalore, “Ever since my association with the Government, I have felt the need for encouraging scientific research and scientific work and have, for that purpose, associated myself with various important organizations, like the Board of Scientific and Industrial Research of which I was and am the Chairman. I have also been closely associated with the Atomic Energy Commission. Well, none of you need to think that I know very much about science or atomic energy. But, I felt and others agreed with me that it is helpful sometimes for me to play the part of a showboy. And my association, therefore, did help these organizations in their dealings with the Government.”

He further said, “My interest, as I said, largely consists of trying to make the Indian people, and even the Government of India conscious of scientific work and the necessity for it. Because really the work is not done by me but by the eminent men, my colleagues, who are sitting round about here and who have helped in giving such a great place to science in India. So, I wish to assure you that in so far as I am concerned, I shall help in every way the progress of scientific research and the application of science to our problems in India.”

ALSO READ:

These were not lip services. Several institutions were created, new departments, and funds were released, and scientists were given certain autonomy and given decision-making powers. Nehru knew that science and technology held the key to future development.