Saleem Rashid Shah

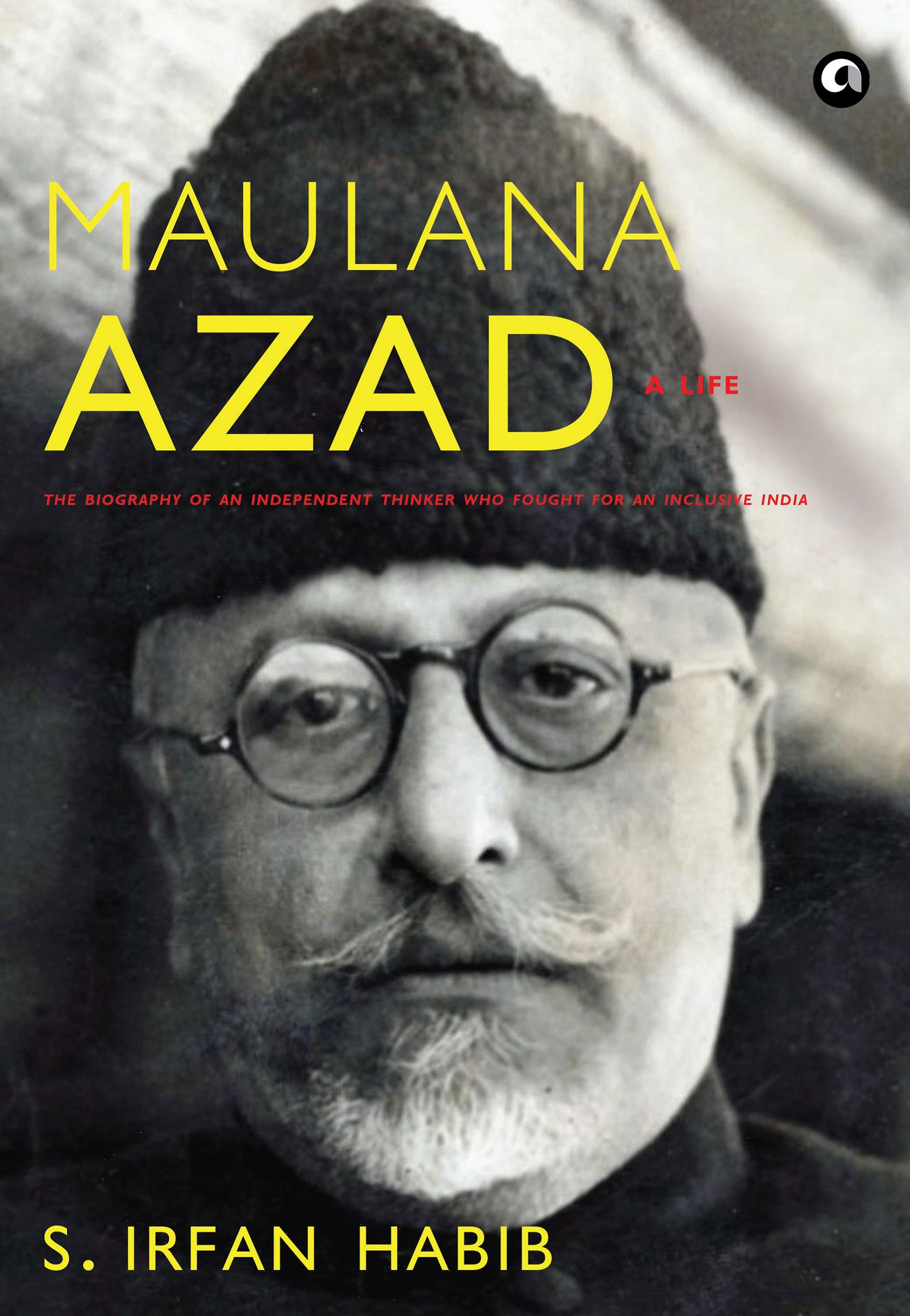

Many books have been written about Maulana Abul Kalam Azad but Maulana Azad: A Life by S. Irfan Habib stands out from the rest as it delves deep into his multifaceted personality. Habib brings out the greatness and weaknesses of Azad’s personality and gives a humane texture to the biography.

Born in Mecca in an orthodox family of Islamic scholars, Azad was the youngest of five children with his three sisters and a brother. His father Maulana Khairuddin was a scholar of Arabic and Islamic theology. His religious determinism was reflected in the firm grip he had on the upbringing of his children.

Azad did not attend any madrassa or university; he was taught at home by his father. His life began with a struggle against the family milieu, particularly his father, a Sufi Pir who was surrounded by devoted mureed who would kiss his hands and touch his feet with respect.

Disgusted by this cohort of followers who were blind in their devotion to his father, Azad turned to rationalism. He was inspired by the writings of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, the 19th-century reformer and philosopher.

The cover of S Irfan Habib's book

This was the point of departure for a young and precocious Azad when his thirst for knowledge and a rational interpretation of Islam made his study of Islam both religious and worldly matters. He launched his newspaper Al-Hilal in 1912 which depicted Azad’s understanding of Islam and his anti-imperialist urge which was to soon blossom into a national movement. It is through eloquent prose and deep research that S. Irfan Habib portrays the evolution of Azad’s character from a home-schooled child to a profound intellectual.

Azad is said to have had an eidetic memory, a memory which in Azad’s own words was like a closet with every compartment containing a distinct subject. Whenever information is required at any particular time, says Azad, ‘I open the appropriate compartment and keep the others locked.’

Azad had this enormous retention power, and was always several lessons ahead of his classmates, including his elder brother. His teachers were both irritated and surprised at Azad’s capability to remember and thus had to give him separate lessons.

Azad’s early journalistic as well as Islamic worldview was impacted by Syed Ahmad, Jamaluddin Afghani, Mohammad Abduh, Altaf Hussain Hali, and Shibli Nomani. The author says that Azad was, in many ways, the total of the different figures he grew up around. He was a skeptic all his life and to him, doubt was essential for the progress of intellectual development.

He would later on critically evaluate everything that he had received as an inheritance. It was the same approach that Azad employed in his understanding of Islam. He was convinced that the path to questioning one’s faith always starts with doubt and ends with denial and those who cannot proceed are bound to face despair. Azad confesses that he underwent a similar phase but did not give up or get trapped in pessimism. He cites a Quranic verse to make his point: ‘The worst creatures in God’s eyes are those who are wilfully deaf and dumb, who do not reason’ (8:22).”

S. Irfan Habib dedicates one chapter to Azad’s epistolary book ‘Ghubar-e-Khatir’ (The Dust of the Memories). Writing this book in the form of letters to his friend Nawab Habibur Rehman Khan Sherwani from Ahmednagar Fort prison, Azad delves into apolitical subjects like virtues of staying cheerful, philosophy of life, merits of solitude, gardening, tea, music, and even about some resident sparrows in his cell. A notable feature of these essays is that Azad writes about each one of these subjects as an expert.

Ghubar-e-Khatir says the author is an extension of Azad’s inclusive approach towards an India he had fought for since the mid-1920s. It was during this internment at Ahmednagar Fort prison that Azad even revised his magnum opus ‘Tarjuman’, a commentary on Quran.

In the run-up to India’s independence, Azad remained a strong voice in favor of composite nationalism and rejected the demand for Partition outright. This strong opposition to the idea of Pakistan brought him into the crosshairs with Jinnah and his Muslim League. Jinnah even went to the extent of terming Azad as ‘The Muslim show boy of Congress’.

Despite being mocked, jeered, and dismissed, Azad ignored Jinnah’s abusive retorts, even when he dubbed him as the show boy and an agent of the Hindus. He remained committed to the fact that religion alone can never be the basis of nationhood. This fact was never as relevant in the past seventy years as it is today.

Toward the end of the biography, the author talks about Azad’s failing health due to his sedentary lifestyle of remaining glued to his books for years together and paying little attention to his physical health. A fascinating figure, a profound intellectual, and an unrelenting nationalist breathed his last on 22nd February 1958 at 2 am.

S. Irfan Habib in his 270-page long biography of Azad, humanizes the account and gives the reader a glimpse of the tender personality behind an indomitable leader of the Indian masses. As independent India’s first Education minister, the author talks about Azad’s pivotal role in strengthening the country's weak education system through initiatives aimed at primary and adult education. His efforts towards the scientific and cultural advancement of the country and his contribution to the arts and culture of a newly independent India have been thoroughly dealt with in the book.

BOOK Review: Maulana Azad: A Life, S Irfan Habib, Aleph Book Company, English, 319 pages