Atir Khan/New Delhi

Tamim Ansary is a world-renowned historian and author who was born in Kabul in 1948 and lived there till he was 16 years old before moving to the U.S. with his parents. Today he is the author of many bestselling books. His phenomenal work Destiny Disrupted, a book that tells the story of world history through Islamic eyes, has attracted world attention. In an exclusive interview, Tamim spoke to Awaz-The Voice Editor-in-Chief Atir Khan about his reflections on the Muslim world. Excerpts:

Let me ask you about your personal story, which is quite fascinating. From Afghanistan to San Francisco. Please tell us about your life's journey.

Well, you know, first of all, let me just mention I was born in Afghanistan; my mother was an American woman from Chicago. And my father was one of the earliest Afghans to be sent abroad for Western education. My mother was the first American woman to marry an Afghan. So, two world cultures overlap in my life, in my consciousness, and life. So, my preoccupation throughout my life has been to think about what happens in these zones where cultures overlap. I came to America for high school and finished college here. And then one thing after another happened that prevented me from going back to Afghanistan.

First, there was a coup, and it just got worse over time. The first time I was able to go back was right after 9/11. I'd like to just say a little bit more about Destiny Disrupted the book that you brought up and about The Invention of Yesterday.

In Destiny Disrupted what occurred to me is that the idea of the history of the world depends on who you are and where you are. And I wanted to illustrate that by saying, look, if you think the center of the world is not Western civilization, Europe and its offshoots, if you think the heart of the world, the center of the world is the Islamic heartland, let's say the territory that stretches between Istanbul and the Indus River you know, you think that's where the center of the world is, then what does the history of the whole world look like? And I wanted to tell that story and I think that's the story I told.

Cover of the Book Destiny Disrupted

In Destiny Disrupted, you mentioned that Islam was the last free religion because it was the beginning of the age of reason-based religions. But today we see emotions have become more important rather than tolerance, which Islam fundamentally teaches. How do you explain this?

Well, I think, the history of the Islamic world went through a period when the Sharia had been very codified. And so, it was everything that you could do in life. It was thought that you could go to the Sharia and some scholar would be able to tell you what is the right decision. So a religion that gets encrusted like that no longer has the freshness of everyday life. You know, it doesn't enliven everyday life. People want religion to be something that makes them feel more alive, more human, more full. So Islam was ready for a renewal of that sort in the 1700s and 1800s. But as it happened, that was also the period when Western expansion had colonized much of the world, and that includes the Islamic world. So, religion became intertwined with anti-imperialism. If you're one of the colonized people, you want to struggle against that.

It also happens to be the case that Islam is very essentially about how a community runs. And, you know, some religions are much more focused on you as an individual, what can you do as an individual? And everything else is separate from that. But Islam is very much and has been from the start about how a community can live in harmony.

So that's what it's all about. There's a natural mapping of the political urges of people who have been subjected to imperialism, to look to religion, to get involved in both of those fears. How does a community run and what do we do about this outside force? So, at some point, there emerged a strain of Islam that nowadays people call Islamism, you know, and I think about that often in terms of Afghanistan. And I would say that it's an example. Afghanistan is an example and can stand for many other societies in Afghanistan at a certain point when the society was having trouble functioning healthily.

Because it was on the line of the Cold War between the West and the Soviet world. The Communist world. And, you know, the communists said, we have an answer for everything. And the Western world said, no, we have an answer for everything. And there was a movement within Afghanistan that said Islam has an answer for everything. And it cannot replace not just democracy and communism but all of that. So that was a political movement in Afghanistan. And so in Afghanistan, how that played out was that at a certain point, the communists were anti-Afghan. They overthrew the government and took over and then the Islamist parties became the mujahideen that fought that government. And they all became much more politicized than religious fights.

I don't think Muslims are alone in that. I think all over the world, what we see are people cocooning within their systems of belief, whatever those might be. I'm going to refer now to the book that I wrote after Destiny Disrupted. I'm going to talk about The Invention of Yesterday. When I wrote Destiny Disrupted well, I wasn't out to tell people that Muslim point of view. I'm writing as a historian, you know, I'm not here to argue for anything. Right. And what I was interested in was when we talk about the history of the world, we're talking about how we get to where we are right now.

Author Tamim Ansary

if we could understand the story of how we got to where we are right now, we can better understand what to do now going forward. So, with Invention of Yesterday, I asked, where are we right now? And the most important thing about where we are right now, it seemed to me, was that we started as lots of little bands of people who were all related and were moving around in a world that was so big, we never thought the wilderness would end. It was much bigger than we could imagine. Yes. And we are now in a world because of technology with any human being anywhere on earth might interact with any other human being in cyberspace, no matter what culture they're a part of. So, every person is exposed to every other culture in a way. And that's too much. You know, that's too much for any person.

If you're in a room where there are a hundred different bands playing different songs and all of the sound is hitting you, you're not going to hear music right? You're going to hear the noise. And we don't want noise. So, we want to cocoon with the people who are like us. So that we can have a life that makes sense, but the problem is that we are now in a state where all of our problems are not just the problems of our group; they're the problems of all humanity. So we have to interact somehow with people who are very different from us. How do we do that? We can't do that by just letting go of who we are..

Then, who are we? That's a problem. My brother is much more of a devotedly religious guy than me. I should mention that I am a secular person; I'm not a religious guy. So, I just want to put that on the table. But my brother, once he's very much of a kind of almost born-again Muslim, and he's a Muslim scholar. He once said, that if everybody were Muslims anything in the world would work. The problem is: we're all not all one thing; that's the problem for Muslims.

As for everybody else, how do we be with our people in a life that makes sense, interacting with other people who have a different way of life and all of us together, somehow being a larger community that works? Right now, you know, when I said that my interpretation was that the idea that Hazrat Muhammad was the last revealed prophet, the last prophet of revelations that, you know, there's two ways to interpret that. One is whatever he said is the final word. So, nothing must change after Prophet Muhammad. During his time was a narrative that you can look for deep principles and in how that unfolded and on the basis of deep principles, guide your way forward in a world where things change no matter what you do. It's not going to be now the way it was back then. So how do you continue to have a moral and ethical continuity in a world where every time some new instrument is invented, it completely changes the way life is lived? Right now artificial intelligence is such a huge thing about how our life is going to change.

If you take an interpretation of your way forward based on the material circumstances that existed, let's say 1400 years ago, it's not going to make any sense. You're not going to be able to function in a world like this with these instruments that we have. You have to stay relevant to the present an ever-changing moment. So, you know, that's what I'm concerned about these days.

What has been the effect of social media and the Internet on the Muslim identity and where do you see it going?

Well, I think this is a Muslim identity and social media is a subset of the larger question of social media and identity. I have to say this- I was born in 1948 in Afghanistan, and the world that I grew up in was a divided world. In the world of my childhood, everybody lived in some domiciles surrounded by walls that shielded us from the public out there. So, there were two worlds. There were us guys in here, and there were those guys out there. Us guys in here were all people who had some personal relationship. And it wasn't just the people in our particular compound surrounded by walls. It was all of us in this compound, that compound, the other compound, our village. Beyond that, there was a private universe that we all belong to. And then there was a public universe. And Afghanistan being a mountainous land that is the people can't interact with far away folks so those who were right there interacted intensely.

Author Tamim Ansary

But at the same time, Afghanistan is between India, Iran, Turkish, Central Asia, and China. Everybody's armies came through our land. So, we had to deal with us, guys. And also diversity. Sure. And then we had the answer in my childhood in Islam because although we had our inner world where it was us folks and we were familiar and we knew each other and in fact, we could trace how everybody was connected. You're the second cousin of the aunt of my grandfather's descendant, blah, blah, blah, you know, we knew that kind of thing. Close-knit, but at the same time in Afghanistan, everybody was Muslim, all the different little networks of people were Muslim. So, everybody knew, you know, five times of prayer at a certain time it's Ramazan.

You're not going to be seen eating bread out there. You know, that's an insult. So, all of those things were part of a public world we all shared. Right now, we have a problem in the world as a whole. We don't have a public world we can all share. Right. And we also have a technology that's coming into our private world to such an extent that we have no private world anymore. The problem that Afghanistan faced was a problem that the world is now facing. Now. And in the course of my 75 years of life, what happened in Afghanistan was that change came so quickly. It's like I was born in a country that was pretty much in the Middle Ages in terms of the technological advancement. And within 20 years, much of the 16 years of my childhood and the next ten years that country went through so much change. The society couldn’t sustain that much change that quickly. And now the whole world is in that amount of change; it is hitting all of us and we're struggling to keep up with it.

The Western world, especially Europe, is getting a bit uncomfortable due to the presence of Muslims and their settling there. How do you see this phenomenon?

I think this is an intensified moment of the problem that I've been talking about the whole time we've been having this discussion. I think that is a phenomenon I've noticed and I'm just going to remove it for a moment from the Muslim refugee crisis, just so we can see it. I remember that after the Vietnam War, the Vietnamese refugees came to America. People are only welcoming strangers when there's few enough of them that they can say, oh, this is interesting. It doesn't change my life in any way. I remember when there was a wave of refugees coming out of the Muslim world, basically across the Mediterranean, that's kind of when there was a crisis and it never stopped since then.

Two things I predicted then: one is it's going to empower the right wing and all of these European countries, they're going to start saying we're going to get rid of these foreigners. the other thing I thought was, and I see it up close with Afghan refugee families is that the kids of families that migrated into the West, even if the families are not doing well, you know, they're not necessarily poor. They're educated people who come very often, they are doctors, engineers, and government officials. They ended up driving cabs or washing dishes in a restaurant here. The older folks and then the younger folks, the new generation, those born here, they went to school and they had to face discrimination against them. If they adopted the narrative, if they saw their life within the narrative, that was the Western narrative, who were they in that narrative?

They were going to be the underclass; they were going to be if they really worked twice as hard as anybody around them, maybe they could get a job and start working their way up. Whereas up and then they wouldn't fit in with their home environment. You know, then they would come home to their parents and their uncles and the older generation would say, what's wrong with you? They would say to them you've lost the ways of our people and that they were pretending. One guy told me when I go home I pretend to be an Afghan. Then I go to school and I pretend to be an American. You can't live your life as someone who is just pretending.

I know a lot about that, you know, because I was born in the U.S., you know, and when I was in Afghanistan, my experience was, well, I'm not an Afghan. I guess I'm an American and I came here and I was like, well, I guess I'm not an American guy. I must be an Afghan. So, you know, I understanding that. So, then you have radical or politicized Islam coming in and offering a narrative.That narrative at the most extreme level tells people you're part of a very special privileged small group. They tap into the origin of Islam, Prophet Muhammad had very few followers, and they were being oppressed in Mecca, they moved to Medina, and because they lived, as God said, you should live, they were empowered and they became the elect of the next generation.

Obviously, that's a powerful narrative for people when their only alternative is you're a poor guy who was nothing. And if you work hard, you'll be the lowest rung on the ladder that the rest of us are way up here. No, that's not going to work. Right? So, you know, but then the thing about that, that crisis with all the refugees coming to Europe is that's the chickens coming home to roost from imperialism because where they came were the countries they went to their countries and said, we are the boss here; we're going to set up a private club. You can't come into this club, you're one of the natives. So, you know, of course, they came and there was going to be problematic blowback.

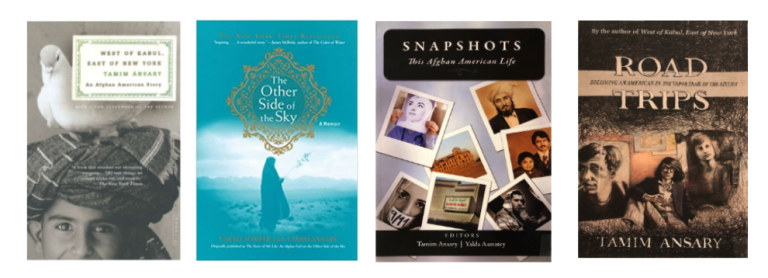

Other books of Tamim Ansary

So you talked about the Muslims keeping themselves relevant. How could Muslims stay relevant and make themselves compatible with other world societies?

Modernization meant one particular thing. It meant secular thought and science and industry and technology. That's what modernization meant. Right. And my father would never have tolerated anyone questioning that he was a Muslim, but he told me when I was a kid thatt Islam is really about being honest. You can't lie or cheat. You have to treat your neighbour well. You have to contribute to your country the way you best can. I like to think of my father as a fundamentalist Muslim. That's the fundamentals that I see there, but I do see that everybody needs more than technology and material goods.

I think this is the thing that people that you know, that in part comes from, you know, there is something about that feeds that fuels and gives energy to radical movements that even turn to violence ncause what we want is not just food. I mean, we want food and shelter and those things but in the world of technology, that's not what we're getting. We're getting a lot more than that. Some of us are getting fancy cars and a lot of things and there's a point at which none of that really matters. What matters is in this earth of ours to have a place where you feel at home. It has nothing to do with material goods; it has to do with your relationship with other people, you know. So there has to be a way in which people can be part of the community where they feel comfortable with others. They know that we share beliefs and so on.

We share rituals we have a sense of ourselves, us as being related to one another. And when we're in our place where we feel at home, we feel comfortable with people we meet, even if we don't know them because they're somebody we might get to know and we could be friends with this person. There are other people who we don't know who they are, or how we could ever know them. That's ok. That's the world. There's going to be people. It's not going to be part of our home world, but we can't let that public world eliminate the possibility of having a home here in this world.

I'm now going to now zero in on Afghanistan because that's the metaphor for me always. In Afghanistan, the Soviets came in and they killed people, they destroyed stuff, and they built roads, power stations and stuff. Their idea was once we get material goods pouring in, people will say, ok, we'll all become Communists. Of course, that didn't happen because what they didn't have anyway, any clue to was how to build or how to contribute to their being in Afghanistan, a place in which Afghans felt at home. America came and said, oh, the communists are bad. They did a lot and they kind of did the same thing. They said, as soon as we have enough, as soon as we get cars and electricity and, you know, sewage systems, which are all good things, we want those things. But that's not enough. And they didn't they didn't have a way and they didn't even have an understanding. I say they I guess I mean, they didn't know what they could do to make Afghanistan a place where Afghans felt at home.

That's something only Afghans can do with each other. So, all over the world, that's the enterprise for all of us. And in every Muslim community, everybody has deep roots going back into the narratives, mythology, history, and storytelling of Islam and they can't just be severed from that. You know, the home that you have and the life that feels like you have a home.

Israel's relentless pounding of Palestine and its innocent people has shown that Muslim world solidarity or Ummah, as we call it, is more of a notion rather than a tool of real support for the community. What does this tell you about the Muslims today?

I'm going to tiptoe around that one because that situation is one that I know I have been watching Israel Palestine all my life and waiting for the next World War to come from there and you know, I wrote something about Gaza, and Israel in 2014 or 12 or whenever it was, there was another time. It's not as bad as this time. I wanted to say then as I want to say about many situations in the world, there are circumstances there that generate this violence and unless the circumstances change, the violence is going to happen no matter who takes what side. And one of the circumstances there is that Gaza is a prison camp. You know, it's 2 million people in a prison camp. They can't leave, they can't go someplace else. They have no way to set up an economy there. There's not enough land to have in that cultural economy. If there are jobs, it's somehow a job that has something to do with the Israeli economy.

What's going to happen there? You know, if this war succeeds and in eliminating Hamas, there'll be another Hamas, it might have a different name, but that's generated by the circumstances at the same time. I want to clear that up. I'm not on board with people marching and saying, gosh, the Jews know this. The Jews have also 2000 years worth of every place they've lived. They've been plundered. Their communities have been trashed, they've been killed. Look, there's a problem going on here. The problem has to be solved more deeply. Even when I say that, I say right now we have to do two things cease fire, immediate cease fire. Pull back all Israeli forces and there's a job for Israel to do to get rid of right-wing government.

We've all read Samuel Huntington's ideas In The Clash of Civilizations. Then Tariq Ali wrote about Clash of Fundamentalism, how, according to you, can be conflicts arising between Islam and the West be resolved in future.

I think there is a process by which different communities develop a language that all are using and it takes time. It takes lots of individual interactions. The reason is that when we use language, we think we're talking about the same thing. But actually, the words we say are only the tip of the iceberg. There's a hidden part, which is all the context that we have in our memory, you know, context and we know and the other person doesn't. So when we're talking about the same thing, we're not talking about the same thing. So, we have to develop a language. Right now, we're in a circumstance where every culture on earth is part of this conversation that's trying to develop a language and we can't get there overnight. So, I think we have to constantly look for how this looks from the other person's point of view.

We have to see the other person’s point of view and we're not going to be able to do it all the time. And, you know, my own little piece of what I can do in the world has everything to do with trying to tell the story as it looks from the other point of view. I'm just trying to I'm trying to do that and that's the only little thing I can do. Sometimes it feels like, well, I spoke my piece and nobody heard it. So I trying to understand myself. So everybody needs to do some of that at the same time, you know, there's no getting around the fact that we're moving into crisis areas in so many zones. On our planet. And, you know, Gaza is one of those places where there is no moment at which it is too soon to stop the bloodshed because every moment increases the difficulty of stopping the bloodshed later.

You know, and I remember in Afghanistan, one of the things that occurred to me during that era was when the Mujahideen were fighting the Soviets, so there were like 80 different political parties in Pakistan that were receiving money and funding some number of fighters in Afghanistan. But within Afghanistan, there were more than 80 armies. You know, there was every warlord that had a little army and so many people were being killed, not by the Soviets, you know, by the Soviets, too, but so many were killing each other. The thing is, you know, people were able to remember not who killed my brother, but what ethnic group killed my brother. So that when the next time they saw any one of that ethnic group, you guys killed my brother, not this particular person, but those guys. And the more that there is killing, the more those settle in and become fixed in the minds of the people who are going to come later. Yes.

It's like I had a friend who went back to Afghanistan and after 9/11, he was at a party and there were some warlords sitting in a place and he accused the guy. He said I know who you are. You and your man. You killed my brother. That also I just put it that way. Right. And the guy said, well, very possibly, I've killed a lot of people. Which one was your brother? And you can see how that is going to be very difficult to get to a peaceful moment between those two people.

Author Tamim Ansary

What is the future of Muslims? How can Muslim youth position themselves in the changing world order? Today, no civilization appears to be perfect. How do we grapple with the inadequacies of the post-modern world?

You can make sense of your own life by seeing what character you are in a larger story that's unfolded and it's difficult for each person if there is no coherent larger story that's unfolded. I think what we can each do is contribute to the story we feel we're part of. And I would say that, you know, for me within the Islamic context, it's really important to continue to work out in one's mind and one's own life what it means to be part of a project, and in history that is the perfection of a harmonious community.

How do you do that? All right. And I think that and the origins of Islam, that question was only being posed within that community. You know, and when it went out from its own community. The early answer was, well, we're going to have a fight. And there is going to be a war, but we have to win the war, because if we don't, then they'll be smashing us. That was the idea of jihad at first. You know, you defend yourself, right? And then to my mind, at a later time, you know, the jihad idea, which wasn't used much in early Islam, but you know, let's just look at that word for a moment. Jihad means struggle, you know, and then and among progressive Muslims, often they have said that jihad refers to the struggle for goodness within yourself. Right. And I think that's inadequate. I think that's inadequate. I think we should look at the fact that or I'm struck by the fact that progressive leftist, you know, communities and movements in history in recent times, the word struggle has been used in those movements. And that word in that context has meant to commit yourself to seeing to it that justice prevails in the system.

You should be involved and not just being good yourself. Charity is not enough. You know, now the system that rules the community, your part of the society, part of that system has to be just. And so, you have to take an interest in that now. So now different people live in different societies, but everybody can have some relationship to being committed to seeing justice increased in the system that you're part of, whatever that system is. I think that, you know, that there are many scales. It's a fractal thing. Everybody can be not just good in themselves but part of the system of justice within, let's say your family network. You know, it's not it's not just you. It's everybody that's part of your intimate world. Then within that, you should be interested in the policies and rules that are promulgated. Let's say at the city level or whatever your next level up is. Those also need to be just and you part of it. I'm all for democracy. But let's not think of democracy as you go to elections, let someone in and that's a democracy. You know, democracy means you're participating in the struggle for justice in your community. And everybody's a part of it. You're not excluded from that.

What are your reflections on Afghanistan today?

I have two thoughts about Afghanistan today, and one is I'm not I wish it were different. You know, I don't want to go to Afghanistan ruled by the Taliban. I think it's time for other people to stay out and let Afghans figure out what they want to do. And, you know, they have to go that way. My heart goes out to many people in Afghanistan who are suffering. I might like to go to the extent that I can do something, it isn't about overthrowing that government and putting in another better government. Because I can't do that. You know, overthrowing that government is only making war. And, the extent to which anybody could help Afghanistan, I always support nonpolitical things, you know, like anything that can be done to help agriculture, medical or well-being (of people); these are things that are not political.

ALSO READ: “There are no FIRs in our village,” Fauji Khan of Haibatpur Village

I guess I have faith that Afghan society has a really strong progressive impulse. If left alone that will emerge when it's fighting off outside orders. That always strengthens the non-progressive; it strengthens the autocratic, tyrannical, and deeply conservative. It's like the Taliban who are in power now. They have no idea what Afghanistan was like in my childhood. They weren't there. They were in refugee camps. Yes. They were people who suffered the worst childhood on Earth. You know, their cities and villages were bombed. They were the kids who, with their parents, went across a landscape littered with landmines that were deliberately made to look like toys so the children would pick them up. This was what the Soviets did. And then they ended up in these very squalid refugee camps with a memory of a childhood in a village that they can easily assume was a golden age. It wasn't the golden age, but, you know, what would they know? So now they think they're in charge and they're going to they're going to turn the country into what they want.

Right. And what is what is going to be your next project? Are you working on any new book or what what is going to be your next preoccupation?

I think I'm up. I can't tell what my next project is going to be. I think I might want to just write a little handbook on how to write for people.