Rana Siddiqui Zaman

Siri Fort Auditorium, New Delhi, in 2014m, was the venue for a concert of jugalbandi (jamming) between Ustad Zakir Hussain and sitar virtuoso Niladri Kumar. An art and film critic, yours truly was invited.

Before reaching the stage, he hurriedly headed towards the green room when we spotted each other. “Asslamuailum Zakir Bhai”, I extended the greeting. ‘O’!' Zakir Sahab stopped; an assemblage of no less than 50 people– the organisers, the guards, the public relations team, and special guests at the event, some from the Ministry of Culture - was with him.

He extended his hand ‘Arey walekum asslam!’ and gestured his palm for the greeting politely and in adab (graciousness) that cultured gharanas of musicians are known for. Delhi largely doesn’t have a culture of greeting in salam, unless you are in a predominantly Muslim-populated area. So, his sudden halt was understood.

“Rana..I reminded’! “Yes, Yes Rana jee. You emailed me (in the US)?’ He stopped in all his politeness. The entire assembly came to a halt. “Kaisi hain aap”? He shook his hand with dropped eyes. He stood like I was more important than him. I was overwhelmed. “Jee aapki duain hain. Interview abhi kar sakte hain” (I am good, Could I interview you now?) I asked.

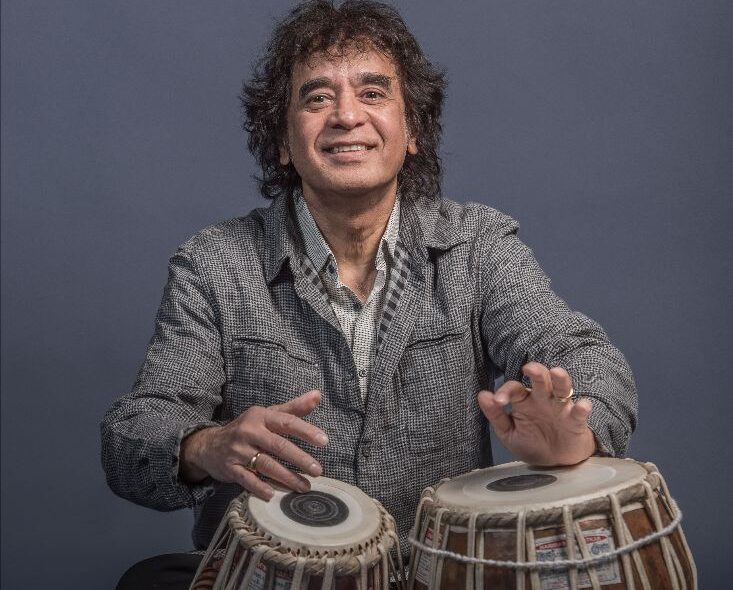

Zakir Hussain

Zakir Hussain

I knew that each minute was precious. “Aayiye. (Please come) Can we finish it in five (minutes)? He asked. ‘In three’, I said. We laughed and he allowed me to walk ahead of him. He made a gesture of “You first”. It was overwhelming again.

As we entered the green room, one, he looked great in a pink shirt and sports shoes. “I am not used to seeing you in such a dress. It’s good for our photographer for a change.” He laughed like a child. His round eyes closed. His frizzy, curly hair waved. “I don’t want to look like an Ustadji all the time! I have an English wife, you know that na? Unka bhi dhyan rakhna padta hai (I have to take care of how she likes me to dress up too). He smiled naughtily like he was just kidding!

Zakir Sahab looked weak. “You look pulled out” I enquired. “Yes, I have some health issues, and don’t make them public you see. I have not been keeping too well of late. I eat less too. I have a strict diet regime. But my tabla keeps calling me. I can’t lie down for long. I follow a strict fitness rule. Our hands and fingers are our strength. We can’t afford not to take care of it. Of late, due to health issues, I am not eating the way I used to....but Allah Malik.” He looked up as if searching for the Almighty to hear him out.

He shared the juganbandi nuances of the concert adding excitedly, “You will hear some new sounds today”, he promised.

The iconic Taj Mahal tea advertisement

The iconic Taj Mahal tea advertisement

Do audiences understand what he plays? We are not educated in classical music and equipment? “ I agree. Most people come for entertainment and see us performing live. But I feel it is an honour that way; despite not understanding the tabla, they enjoy and clap. And the problem with jugalbandi is, people don’t know the intricacies and fineness of the raga we use, the bols, laya, maatra, kayda, syahi... but that’s how it is. We have got to live with it. “

He was right. As the concert began, the stad who had changed to a shimmering yellow kurta with red embroidery on the neckline and white Aligarh-cut pajama dawned on stage to thunderous clapping from the audiences, whistles and greetings!

In the concert that ran for over two-and-a-half hours, the audience in the last few rows, who didn’t understand the finer nuances of the live magic on stage, started to get up to have a cup of tea or restrooms during the concert. A beeline for snacks and tea could be seen from the door ajar. This happens in India in most classical-based events.

However, the ustad had said that musicians have to live with it. But a master will be a master. Without feeling offended, he did what he had promised to me in the green room.

He stopped in between the performances; took the mike in hand to now a pin-drop silence. Perhaps the audience understood how uncouth it was to get up during such a prestigious concert. The Ustad said, “Aap sabke liye aaj kuch special laya hoon..(I have brought something special for all of you)” Within no time, the audience rushed back to their seats. He brought two mikes closer to the tabla and began! Sounds of raindrops were unveiled.

It followed the reverberation of waves and tides of the sea and the thunder of the busting cloud, suddenly smoothening the atmosphere, chirps of the birds in the forest, and chchuk-chchuk of the train filled the auditorium. We travelled from the road to the forest to the river and train, through his magical fingers on the instrument. His signature style of nodding flinging his curly hair in the air, added to the mood. The stage was set.

The younger lot jumped in joy! The audience stood up. His tabla had started talking to the people; the commoners and the connoisseurs. Now the Ustad was playing alongside the constant clapping of the standing audiences, it sounded like a jamming of claps, tabla, and sitar. It went on and on and on, amid collective requests of ‘once more’, till the maestro stopped, kneeling in gratitude, with folded hands in “Thank you”.

I kept observing people bowing in appreciation and audiences screaming “Wah Ustad, Wah!”- a slogan created by the Taj Mahal tea he endorsed, which became a signature tribute for Ustad Zakir Hussain in India and the globe.

(The author is a an independent journalist who writes on art and films. She was formely with the Hindu newspaper)