Saquib Salim

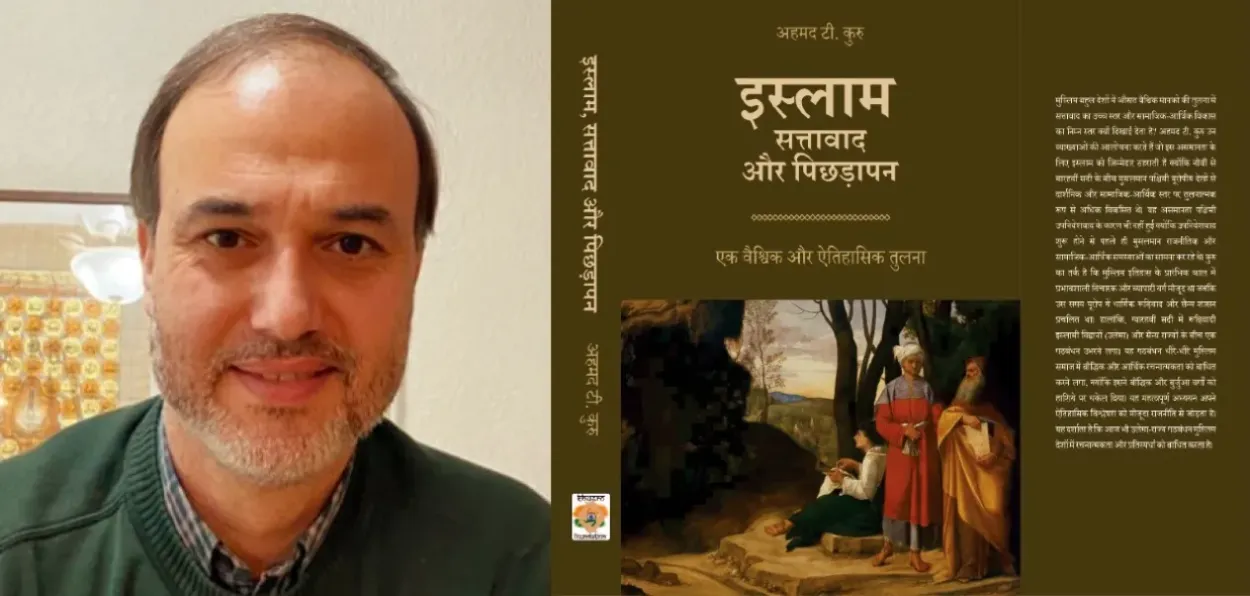

Ahmet T. Kuru raises the question: “Why are Muslim-majority countries less peaceful, less democratic, less developed?” at the outset of his thought-provoking book, Authoritarianism, Underdevelopment- A Global and Historical Comparison.To reach some answer to this, Kuru engages with two most prevalent explanations of this phenomenon; 1.) Several analysts have blamed Western colonialism for the rise of violence in Muslim societies., 2.) “Some scholars have argued that – based on its texts or history – Islam has some essential characteristics that are associated with violence.

Kuru rejects both explanations and instead blames the Ulema-State alliance which, he says, developed around the eleventh century and undermined intellectual freedom and checked the rise of the bourgeois. He argues, “The anti-colonial approach overemphasizes the impact of Western countries’ policies toward other parts of the world while downplaying the role of non-Western countries’ own domestic and regional dynamics. Hence, it cannot explain why Muslims have experienced interstate wars, civil wars, and terrorism by and against other Muslims, rather than simply fighting against Western colonial powers and occupiers.”

In the case of Islam, Kuru points out that the rise of intellectuals and mercantile class during the first three centuries of Islamic rule was enough to show that the religion is not innately ‘violent’ or ‘regressive’.

The author declares, “This is primarily a book of political science, not history. It analyzes contemporary problems and explores history to understand their origins.” However, his analysis of historical texts and contextualisation can generate interest for any history student

I found Kuru’s argument that early Islamic scholars - the ulema - would distance themselves from the state, or ruling elite, to keep themselves untouched from political control, interesting. They either took to trade for finances or were financed by wealthy traders to carry out their academic pursuits. He provides data and examples to bring this point home.

He argues that during the eleventh century, scholars like Ghazali pioneered a theory that religion and state are inseparable.

The idea of religion and state being interdependent, according to the author, was a Persian influence on scholars. And, the idea dominates the common Muslim discourse even today, and any scholar disagreeing with this view is marginalized.

The argument that an independent strong mercantile class supports the intellectuals and the lack of this class in Muslim societies since the 11th century has set in the developments leading to overall decay in scientific development among Muslim societies explains a lot but still lacks more historical inquiry.

Scholars like Brooke Adams, Victoria Miroshnik, Dipak Basu, etc. have pointed out that the Industrial Revolution, which changed the world we live in forever, was fuelled by the money plundered from Bengal by the English after the battle of Plassey in 1757. Several inventions and discoveries were made especially to mechanize the textile industry in England around this time. This supports Kuru’s assertion that an independent mercantile class fuels intellectual and scientific development.

However, Kuru does not engage with two important phenomena. Indian society under the Mughals, who ruled over India during the latter half of the 16th and 17th centuries, held trading castes in high esteem. The traders were largely independent of political influence and carried out trade with far-off lands. An influence of the Indian Caste system, which placed traders as the third most important social group, also ensured that traders enjoyed a certain degree of autonomy. That did not translate in the overall intellectual development of India at that time in the face of the rise of Europe around the same period.

Historically, state-sponsored scholars in ancient India and ancient Greece had led the intellectual developments of their times. Closer to our times, state-controlled Universities, especially in the USSR, provided us with several breakthrough scientific developments. There was no free mercantile class in the socialist and communist countries when these were challenging West Europe in intellectual development in the post-World War 20th century.

Kuru also argues that Muslim countries have more tendency to develop an authoritarian regime, secular as well as Islamist. The correlation of authoritarianism with underdevelopment and lack of scientific development should have been argued more. Readers need to understand how Chinese or Soviet authoritarianism did not hinder such developments in those societies.

The author seems to have caught the right nerve by pointing out that ‘rentierism’ has helped in prolonging “the dominance of non-productive political and religious elites in most Muslim countries. These rents have enabled the survival of many Islamist regimes, which are dominated by the ulema (such as Iran) or by an ulema–monarchy alliance (such as Saudi Arabia). In some other Muslim cases, the absence of oil revenues forced political authorities to reduce state control over the economy and society. But these politicians have generally continued to seek rents and ways of going back to statist socio-economic policies.”

The argument is that governments of these rentier states are not dependent on people’s taxes and thus act in fashions which can be called regressive or static to maintain their control.

I wish the author would have engaged with Indian Muslim society to give insights into this important segment of global Muslims. The fact that India houses the second-largest Muslim population and used to have the largest till 1947 (now divided between India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh) presents it as a case study. Indian Muslim organisations like Tablighi Jamaat, Deoband School, etc. appeal to a large global population.

One would love to see how Kuru would have engaged with the Indian Ulema (especially Deoband) who accepted Mahatma Gandhi (a Hindu) as their leader. Interestingly in the case of India, it was ‘secular’ educated Mohammad Ali Jinnah who wanted a religious state while Jamiat-i-Ulama (Association of Islamic Scholars) largely argued in support of a secular India led by allegedly a ‘Hindu Party’, Congress.

The book is a compelling read. This well-researched book will lead researchers to ask more questions and has the potential to open new floodgates of inquiry. The author poses tough questions, tries to answer and more than that forces his readers to pause and think. He questions the existing scholarship on the subject and prepares a fertile ground for further research.