Neelam Gupta/New Delhi

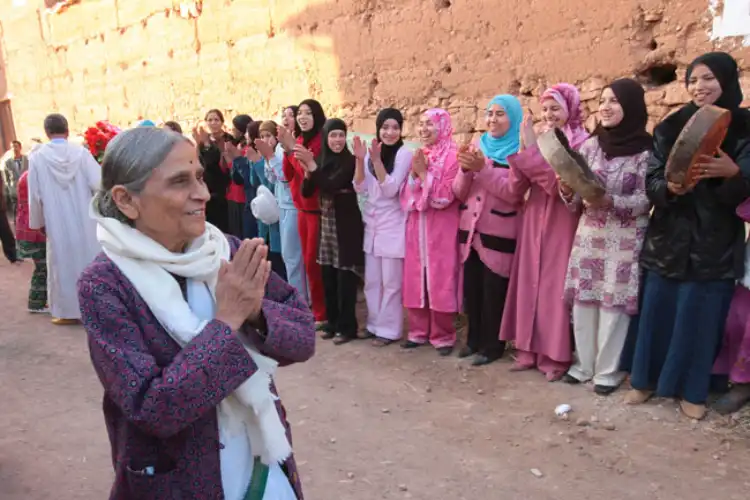

Ela Bhatt, known as India's 'gentle revolutionary' and founder of the NGO Self-Employed Women Association (SEWA) that helped empower millions of Indian women by making them self-reliant, has also changed the lives of at least 10,000 women in Afghanistan.

On August 15, 2021, when the Taliban were storming into Kabul to seal their victory in Afghanistan a second time, oblivious of the changes in the country, six women were busy in an online meeting with the officials of SEWA.

These Afghan women were the master trainers leading a program of skill development for women and organizing them into self-help groups. This association of skilled and financially independent women has grown into Afghanistan’s largest self-employed women’s association.

However, as soon as these women heard the news about the Taliban's takeover, they were shocked and started reliving their experiences of the Taliban’s earlier rule - from 1996 to 200.

An Afghan women selliing jam made by women in Kabul

These 10,000 Afghan women trained by the SEWA who comprised the country’s biggest women’s alliance were once poor, widows and single-house earners from the capital Kabul, Kandahar, and other provinces.

They were left impoverished firstly due to a long war between the Soviet military and the Mujahideen and later infighting among the local warlords. The war left many widows, and orphans and pushed families into poverty.

The Taliban’s first rule made women cover their faces, vanish from public spaces and workplaces, and face punishments like stoning to death, and the world watched the women suffer.

After the Taliban was overthrown and an elected government led by Hamid Karzai took charge o the country, life started changing for women. India and Afghanistan signed a memorandum of understanding in 2004 for mutual socio-economic cooperation.

At this stage, the Indian government approached Elaben Bhatt, whose NGO had made women workers' cooperatives a force to reckon with in India for helping Afghan women.

Kabul women Women getting trained in making Bakery items in Ahmedabad

Kabul women Women getting trained in making Bakery items in Ahmedabad

SEWA’s senior coordinator Manisha Pandya says when they met these women in Kabul in 2007 for the first time, they looked terrified and were not optimistic about life and the future.

It took the SEWA team comprising Manisha Pandya, Pratibha Pandya, and Megha Desai one year to boost their morale and emerge from the shadows of their past.

Manisha Pandya, Pratibha Pandya, and Magha Desai, who were associated with SEWA’s Afghan initiative say they first did a survey in Afghanistan and zeroed in on three areas: embroidery, food preservation and processing, and flower cultivation.They said that initially 35 women were selected and invited to Ahmedabad for a Train the Trainer program. These women went back to Kabul to start the work of mobilizing and training women.

In the first four years, a SEWA team stayed in Kabul for three months to be replaced by another with an overlapping phase of a few days to maintain continuity.

Motivating the women was the hardest part for SEWA as these women had barely come out of the shadows of an oppressive regime.

“They faced a lot of problems; their families were hostile to their working outside the homes; the markets didn’t value their work and menfolk were forbidding them from moving out for training and association,” Manisha said.SEWA officials started inviting their menfolk to the meetings and gradually conditions improved.

They also spoke with retail businesses and markets to make sure they bought their products.

Soon the women started doing well, they set up a business center in Kabul, and their stuff was in demand in the markets. They participated in exhibitions in India.

Women made garments on display in a store in Afghanistan

Thirteen years of association with SEWA had changed the lives of these women; their children went to school; provided for their families and lived well.

Seeing this success story, the Afghan government asked SEWA to extend the program to far-off provinces of Mazar-e-sharif, Herat, Kandahar, Baglan, and Parwan.

Today there are 450 Afghan Master Trainers in Afghanistan to expand the network and yet the return of the Taliban has cast a shadow over the program. The SEWA team that interacted with Afghan women on August 15 said they looked confident and cheerful but the next day their countenance had changed. Having become financially independent, this time they are not ready to put up with the Taliban’s misogyny.

Shikiba of Kabul said, "After the Taliban were gone, SEWA made her strong and helped her rebuild her life. Today, when the Taliban is back, I believe we are strong enough to rebuild our lives in safer areas."

Sosan of Kabul said, “I wish for a safe passage out of Afghanistan. I am confident that in a new place, I will start work and stand on my own two feet and sustain my family. I fear for my safety, I fear for my family's well-being, and need help."

Azizgul from Herat said, "Ever since the Taliban took over, women are not allowed to step outside their homes anymore. The situation is very bad as fear over rampant killings and gunshots. For us, the only way out is to get out of the country.”

Azizgul said their families also want them to leave the country. “They don’t want to see us pushed back into a life of oppression and suffering, " she told her SEWA counterparts in Ahmedabad.

Afghan Women making garments in a women-run factory in Kabul

Kabul-based Hafiza Jan, the executive committee member of Sabah Bagh-e-Khazana Social Association (SBKSA), sister organization of SEWA at Kabul, and master trainer of garment making team says the recent developments brought back spine-spilling memories of her being knocked down by gun-wielding Taliban.

Today there are 450 Master Trainers in Afghanistan to expand the network and yet the return of the Taliban has cast a shadow over the program. SEWA officials in Ahmedabad say the Taliban’s return has changed the situation. The women from places other than Kabul are not in touch with them anymore.

They say it’s difficult to contact women even in Kabul due to poor network connectivity.

(This is the edited version of the story published last year)