Tarique Anwar/New Delhi

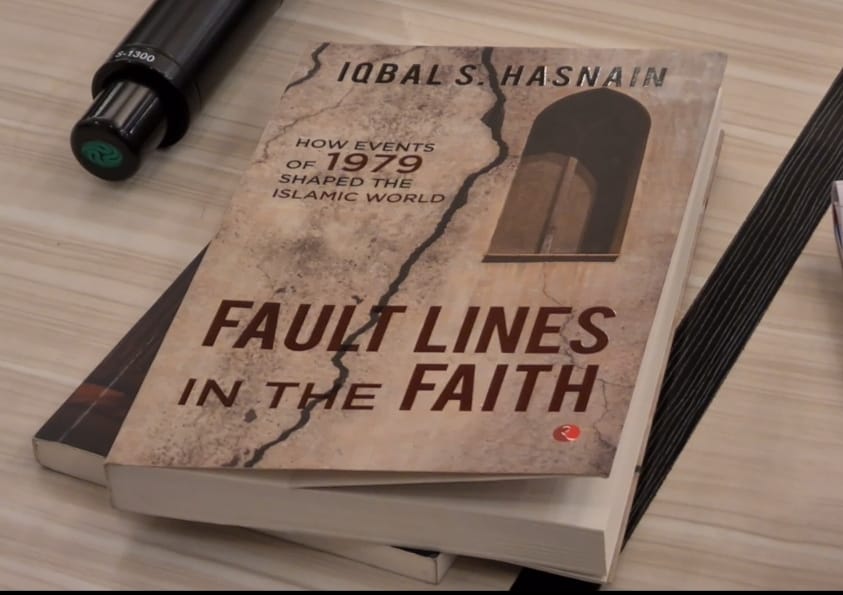

The year 1979 was a pivotal moment in the history of the Islamic world, setting off a chain reaction of events that continue to shape global geopolitics. In his latest book, Fault Lines in the Faith – How Events of 1979 Shaped The Islamic World, Professor Iqbal S. Hasnain, a geologist who has researched Himalayan glaciers and climate change, narrated how this fateful year became the bedrock for the modern-day conflicts, ideological shifts and the rise of “global jihad”.

Three key events in 1979 — the Islamic Revolution in Iran, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the siege of the Grand Mosque in Mecca — set the course for the “radicalisation” of Islam and the emergence of “violent jihadist movements”.

“Unlike Christianity and Judaism, Islam found itself entangled in the cycle of global terrorism, largely driven by the radical Salafi ideology,” he writes. His book traces the ideological, political and military consequences of these events, offering an academic yet accessible analysis.

Iranian Revolution and Sunni-Shia rift

The book opens with an exploration of the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, an event that, according to the author, sent shock waves across the Sunni Arab world. Hussain writes with Ayatollah Khomeini’s rise, Iran’s theocratic government sought to spread its influence among Shiite populations across the Middle East — alarming Sunni-majority states. He explains how, in response, Saudi Arabia doubled down on its commitment to Wahhabi-Salafism, propagating a “puritanical and rigid interpretation of Islam that has since fuelled sectarian violence worldwide”.

The author traces the roots of this ideological battle to Ibn Taymiyyah, a 13th-century Islamic scholar whose “strict interpretations” of Islamic jurisprudence “laid the foundation for Wahhabism”. This ideology, according to the writer, was later embraced by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, who “formed an alliance” with Muhammad ibn Saud, the founder of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. He says they together established Wahhabism as the state-sanctioned doctrine, which continues to shape Saudi religious policies today.

Author Iqbal S. Hussain with IICS chief Salman Kursheed at the launch of his book

Author Iqbal S. Hussain with IICS chief Salman Kursheed at the launch of his bookHussain highlights how the “Wahhabi doctrine”, which “condemns” Sufism and Shiism as deviations from true Islam, played a crucial role in “shaping sectarian conflicts post-1979”.

“Wahhabism underscores an intense hatred for Shias and even Sunni Sufi Muslims, who emphasize tolerance and spirituality over rigid doctrine,” Hussain says. This ideological clash, he claims, gave rise to proxy wars, from Lebanon to Iraq to Yemen, shaping the geopolitical map of the region for decades.

America’s short-sightedness and rise of ‘jihad’

Hussain dedicates a significant portion of the book to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the subsequent withdrawal of American support post-1989. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), in its Cold War strategy, “funded and trained” radical Islamist fighters to counter the Soviets. However, after the Soviet withdrawal, these fighters — many of whom, the author claims, had embraced radical Salafi ideology — were left leaderless and disillusioned. “The literal abandonment of Afghanistan by the Americans after the Soviet retreat left hundreds of thousands of radical Islamist fighters stranded and ready to become suicide bombers under the leadership of Osama bin Laden,” Hussain observes.

He highlights the role of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) in shaping Afghanistan’s trajectory. “With financial backing from Saudi Arabia”, he says, “Pakistan’s ISI facilitated the Taliban’s rise to power, selecting Mullah Omar as their leader and providing military training to its fighters”. “By the mid-1990s, Afghanistan had become a factory for global jihad, training 30,000 terrorists from around the world,” he writes, emphasizing the unintended consequences of American foreign policy.

Once an obscure cleric, he writes Mullah Omar emerged as the Taliban’s spiritual leader who enforced a strict interpretation of Sharia law and offered safe refuge to Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda — ultimately leading to the 9/11 attacks.

The U.S. and its blind spot on ‘Wahhabism’

A central theme in the book is the United States’ failure to recognize the “long-term dangers of Wahhabism”. Hussain questions why the U.S., despite having intelligence reports on the growing threat of al-Qaeda and its terrorist network, did little to counter it before the 9/11 attacks. “It is beyond anybody’s comprehension why the smart strategic thinkers of the U.S. did not flag Afghanistan as a failed state harbouring Wahhabi terrorist group,” he says.

Hussain writes even after 9/11 when investigations revealed deep links between Saudi citizens and the attacks, the U.S. refrained from holding the Saudi government accountable. He attributes this to the “longstanding U.S.-Saudi relationship”, which dates back to President Roosevelt’s era. “The U.S. has always prioritized economic and geopolitical interests over addressing the ideological roots of terrorism,” he asserts.

Sectarianism and Shia-Sunni divide

The book delves into the history of the Sunni-Shia schism, tracing its origin to the time of Prophet Mohammad, a dispute over his rightful successor, and the battle of Karbala in 680 AD. Hussain argues that sectarian tensions entered a new phase with the 1979 Iranian Revolution, which emboldened Shias across the Middle East.

“The U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 only exacerbated this divide,” he writes, highlighting how the removal of Saddam Hussein, a Sunni leader, created a power vacuum that allowed Shiite factions aligned with Iran to take control. The rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which positioned itself as a defender of Sunni Islam against Shiite domination, further deepened sectarian strife. “Sectarianism has become a tool for both governments and extremist groups, ensuring that the region remains in a perpetual state of conflict,” he notes.

“The U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 only exacerbated this divide,” he writes, highlighting how the removal of Saddam Hussein, a Sunni leader, created a power vacuum that allowed Shiite factions aligned with Iran to take control. The rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which positioned itself as a defender of Sunni Islam against Shiite domination, further deepened sectarian strife. “Sectarianism has become a tool for both governments and extremist groups, ensuring that the region remains in a perpetual state of conflict,” he notes.

Hussain also discusses the ideological contributions of Shah Waliullah, an 18th-century Islamic scholar who attempted to reconcile Sunni and Shia divisions while advocating for Islamic revivalism. His works later influenced movements such as the Tablighi Jamaat, which sought to renew Islamic practice but remained largely apolitical compared to “radical jihadist groups”.

Rise of ‘Shia Crescent’ and regional power struggles

The third chapter discusses how Iran’s growing influence, particularly through its alliances with Syria, Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen has fuelled Saudi and Israeli fears of a ‘Shia Crescent’. Hussain explains how regional powers, including Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the U.S., have worked to counterbalance Iran’s growing influence.

“The animosity between Saudi Arabia and Iran is real, but it is often overwhelmed by Arab nationalism,” the author argues, pointing to moments when regional politics overshadow sectarian divisions. He provides examples of how Iran strategically engages with Sunni nations when politically expedient, as seen in its past negotiations with Syria.

Reclaiming a Peaceful Islam: The Role of Sufism

In the concluding chapter, the author presents Sufi Sunni Islam as a potential antidote to “Wahhabism and Salafism”. “For centuries, Sufism flourished as a philosophy of peace, love, and tolerance — building bridges between faiths and cultures,” he writes. He cites examples from Morocco, where the government has actively purged Wahhabi influences from religious institutions in favour of promoting a more tolerant interpretation of Islam.

Hussain advocates for a return to the golden age of Islamic scholarship, where science, art, and philosophy thrived alongside religious practice. “If Muslim societies embrace their intellectual heritage and reject the rigid interpretations imposed by Wahhabism, they can once again become centers of learning and progress,” he concludes.

The book tries its readers understand the complexities of modern-day Islam, the ideological roots of radicalism, and the geopolitical struggles that have shaped the Middle East, with its author weaving history, politics, and theology into a narrative that, for some, “challenges mainstream perceptions”.

With the current Saudi leadership under Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman taking steps to “moderate Wahhabism”, the book questions: Is the Islamic world on the verge of another ideological transformation, or will the fault lines of 1979 continue to dictate its future?

ALSO READ: Hindu woman's donation for mosque decoration wins hearts on social media

Hussain has served as pro-chancellor of Jamia Hamdard, New Delhi, and vice-chancellor of the University of Calicut, Kerala. He is a member of the board of trustees of the National University of Science and Technology, Muscat, Oman.